(Re)imagining a Social Contract for Labor in the Digital World

Kate Lappin & Sofía Scasserra

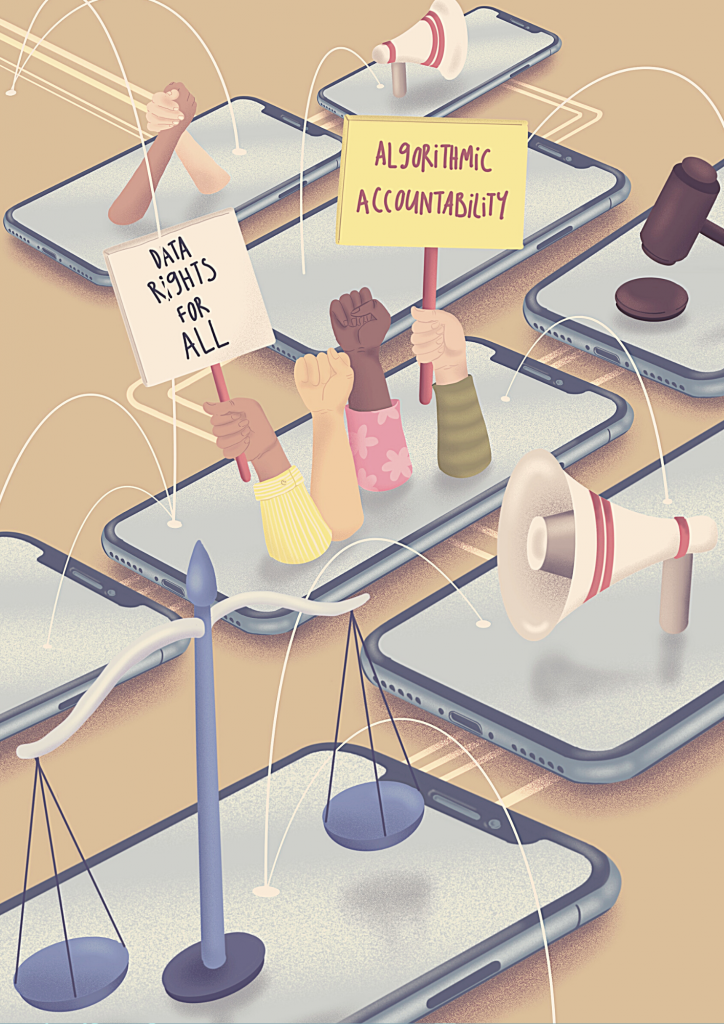

The Digital New Deal project is as much about open debate and exchange of ideas as it is about outlining new treaties, finding new metaphors, and envisioning new regulatory frameworks for the digital. This freewheeling conversation between Kate Lappin, Regional Secretary for the Asia Pacific region at Public Services International, and Sofía Scasserra, advisor to the global presidency of UNI Global Union and the Argentine Senate, belongs to the former category. Placing the worker front and centre, its aim is to think through and imagine new articulations of labor and data rights, new trajectories for trade union movements, and a radically different social contract for labor.

Kate Lappin (KL): Across the world, digital transnational corporations (TNCs), collectively known as Big Tech, are fundamentally shifting the political, economic, and social landscapes of workers’ lives. There hasn’t been a change this big since the industrial revolution. And, like the industrial revolution, this revolution too is fundamentally shifting our ability to organise and exercise power – as workers, as rights holders, and as users of public services. In keeping with the overarching theme of this series, our conversation will assess the ways in which the dominance of digital behemoths is upending workers’ lives through constant surveillance and monitoring, incessant data capture, and algorithm-fueled inequalities. We will reflect on the need for a new social contract that centers workers’ data rights, and the role of labor unions and social movements in this regard. Finally, we will mull over new strategies and alliances that can propel us towards a better future of work. Our focus will be on the Latin American and Asia Pacific contexts since this is where much of Sofía’s and my work is based.

Let us start Sofía, with how you think the digital revolution and the growth of Big Tech corporate power has impacted workers.

Sofía Scasserra (SS): In recent years, the growth of digital TNCs has affected how we communicate, what we buy, and how we work. The introduction of technology into the workplace has begun to subject workers, as you mentioned, to constant surveillance, absorbing data from them and ushering in a new phase of cyber capitalism. And as we know, the data thus accumulated is reconfigured into raw material for developing more technologies that will then replace or discipline the same workers. These technologies are produced largely in the Global North and imported to developing countries in the South. This is what we call digital colonialism, and it forecloses any effective digital industrialization in the Global South. Of course, this is highly dangerous, especially for public services, since the technologies that are being imported are concerned not with social benefit but corporate profit.

The world of work in Latin America is diverse and complex. Informality is rampant and the digital divide has intensified existing inequalities. Some sectors have hyper-technological unicorns such as Argentina’s Mercado Libre, even as entire regions are stranded without internet access and knowledge of technology management. This gap affects the arena of work, since it is not easy to train workers when a new technological tool enters the workplace, often leading to job losses. That said, the state of work in the region is not rendered ‘sick’ by technology and robotics, but by labor fraud. The use of technologies to precaritize, outsource, and overload workers is common across countries in Latin America. This situation is not the fault of technology per se, but its poor implementation and the lack of regulation. And finally, the issue of ‘data as the new raw material’ is starting to ring alarm bells. UNI Global Union and Public Services International (PSI) have both done extensive work on this really important issue. In your work at PSI, Kate, how do you see the lack of regulatory oversight on data rights affecting workers?

KL: You’re right. World over, governments have largely failed to tackle fundamental questions about the value and power of our metadata, what it means for this level of intelligence and control to be in the hands of Big Tech monopolies, and what the role of democratic governments, entrusted with upholding human rights, should be in data governance. Over the past decade, discussions inspired by colleagues at IT for Change have made me consider and compare the changes that workers and communities currently face with those of communities confronted by the enclosure of lands and the introduction of industrial manufacturing in the past.

Both the industrial and the data revolutions involve powerful private interests capturing or enclosing a resource that was previously not a financialized commodity, and consequently amassing even greater wealth and power. It is useful to think about these histories because trade unionism was born out of workers’ struggles in the aftermath of the industrial revolution. It led to better wages for some organized workers and spurred further demands for public services and a more representative democracy. These past gains are quickly being dismantled, often under the guise of technological restructuring.

Many private companies have now acquired a monopolistic hold over the metadata governments need to operate critical public services. Many governments are handing over rights to such data to companies without understanding their value or implications for effective public service delivery. Giving away rights over data to the private sector not only strips the government of potential revenue, but also undermines the capacity to govern, provide public services, and ensure decent work.

Google Maps and Uber hold essential data on city traffic flows, genome mapping companies are collecting massive databases on DNA sequencing required to develop future medicines, and Facebook can influence election results with essentially no regulatory oversight. Global data companies like Amazon, Google, Facebook, Microsoft, and Alibaba and their host governments are pushing for new e-commerce rules to be adopted at the World Trade Organization (WTO). They are backing trade agreements that will constrain the capacity of governments to develop new ways to treat data as a collective social good. Already, rules that civil society has termed ‘digital colonization’ prohibit national regulations for data localization and requirements for digital companies to have a local presence, restrict access to source code, and limit the liability of Internet Service Providers.

The business model of Big Tech companies is based on their ability to effectively rewrite economic rules – they can avoid taxes by directing most of their economic activity through tax havens, they have largely avoided antitrust laws that were designed to stop monopoly power, and they have created fictions like the ‘self-employed worker’ and ‘flexible work’ to get around labor laws.

SS: Also, these rules will weaken the terms of trade, pushing poorer countries to be only the consumers of technology, stripped of any access to data that could help develop and improve their own ecosystems and public policies. At various multistakeholder forums, we are being forced to approve rules that will determine an economy we are only just starting to understand. It is hard to imagine that poorer countries really understand what they are giving away if they sign these rules.

These rules and the new models that are being designed come under the umbrella of platformization of work and are already affecting all employment. When we talk about platformization of work, we refer to a world of work that is mediated by digital TNCs which have legal addresses in tax havens, and act as ‘mere intermediaries’ in the data economy through web platforms. This closely aligns with the WTO’s idea of ‘servicification’ of manufacture, which classifies everything, except the final product, as services. One rather extreme version of this idea will see every worker is a micro-enterprise that provides a service to a company through the intermediation of a platform.

This stance is being resisted in various parts of the world. Even workers who are employed by platforms are finding ways to resist the precarity to which they are subjected. Their victories have taken the form of labor laws that recognize the platform as a company and its workers as dependents, or cooperatives that organize workers in ways that give them more power to decide how to offer their work. Labor unions are also organizing and mobilizing platform workers around the world. In Latin America, platform workers are engaging in different forms of digital activism. They log into work accounts but don’t actually take on work, thus disrupting services provided through platforms. These acts of resistance offer a ray of hope in the defense of decent work. It is only a matter of time before, at least in Latin America, workers have more expansive rights and the power of these companies stands curtailed. But till that happens, Kate, do you see platformization inevitably engulfing other areas of work?

KL: As you mentioned, Sofía, there’s nothing inevitable about the future of work. The World Bank and Big Tech might like to think that precarious, platform-based work is a natural consequence of technologies, but the future of work will be determined in the same way that it always has – through the exercise of power.

Precarious platform work hasn’t come about because of technology – it has come about because tech companies have aggressively undermined labor laws and based their business models on the avoidance of employment obligations. And when workers build collective power, they can challenge the fictions created by Big Tech capital. Tech companies in the US are complaining that their businesses may not be viable if laws introduced in several states to recognize workers as workers, are successful. They are pouring millions of dollars into lobbying against this.

The World Bank’s 2019 report, The Changing Nature of Work, made the case for a form of social protection that would enable platform workers and other precarious and displaced workers to continue receiving meagre, insecure income. They argued that a safety net would allow labor laws to be further deregulated. The Bank used technological determinism to emphasize what it has always advocated for – deregulation of labor and capital. These technological fictions enable the sustained attacks on wages, work conditions, and trade union rights. This will impact (and are already impacting) all workers. When the minimum wage floor is effectively meaningless, pressure mounts for all wages to go down, including public sector wages.

So clearly, workers delivering public services are not exempt from these pressures. Governments are increasingly outsourcing public services to Big Tech. More than half of Amazon’s operating income comes from Amazon Web Services and a growing portion of AWS is hosting government data. Public postal services are being squeezed by Amazon and others who use low wages or the fiction of platform work as a competitive advantage.

During the pandemic, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) advised governments to cut public sector wages suggesting that wages for some private sector workers are lower. As we have always said in the union movement – “touch one, touch all” – when some suffer, all eventually suffer. We know that, by driving down wages and monopolising wealth, Big Tech has played a major role in the exacerbation of various forms of inequalities. How is this playing out in the Latin American context, Sofía?

SS: I totally agree with your assessment that the techno-deterministic view of the IMF and World Bank makes us think there is no alternative than to accept precariousness, because that is the only way the model can sustain. But the truth is that if your business model is sustained by labor precariousness while you get richer and richer, that is not a business model, that is essentially fraud.

Thinking about alternatives is hard in Latin America because governments right now don’t have the capacity to come up with new frameworks on a regional scale, and people don’t have enough digital education.

I think the biggest inequality between workers today is the digital divide. This gap operates between generations, excluding those who cannot adapt to new technologies. Many workers lose their jobs as a result. In some cases training works, but in others, the accelerated rate of change of technology means that many workers cannot keep up.

The second gap is that of access to technology. In Latin America, access is very unequal, not only with respect to the level of income and the quality of the technology that a worker can afford, but also with regard to the infrastructure of public services available in their city. Some have to work for months to be able to buy a telephone or a computer that they can use for work, or they are stuck with old devices without enough RAM memory, unable to run the applications they need to work.

The gap in access to public services is even worse. The population distribution and demographic characteristics of the region mean that huge parts of Latin America are very thinly populated. This has repercussions on the incentives for companies to invest in better internet connections. Fiber optic technology is an essential public service that does not reach most cities and towns. What do we do with the rest, who are not in the big urban cities? The lack of quality public investment in the less populated regions means that only some workers can access better jobs through platforms and teleworking. Workers in regions that remain disconnected are stranded in the periphery of the labor market. What other inequalities do you see in your region, Kate?

KL: I think that’s very well put. To add a couple of points, data monopolies are a key driver in exacerbating existing inequalities. Data companies increase wealth inequalities by extracting and monopolizing much of the world’s wealth, aggressively avoiding taxes which diminishes public services that can actually reduce inequalities, driving down wages, and worsening work conditions. Inequalities between countries is magnified not just by the wealth accruing to billionaires in the US, China, and to some extent Europe, but also by data monopolization that centralizes much of the world’s information (or intelligence) in the US, China, and other data havens.

Then there are inequalities fueled by algorithms. Algorithmic management sounds neutral but often draws on metadata that reflects existing inequalities and replicates it. Secretive algorithms can deepen the power imbalance between workers who don’t have access to the data, and the management which is protected by ‘commercial-in-confidence’ and trade rules that hide the source code. In the case of platform workers, for instance, small changes in algorithms can drastically reduce their incomes for reasons that may remain completely unknown to them.

Workers’ productivity trackers may appear neutral but are generally modelled on the output of a healthy, experienced worker of a particular sex, age, and stature, on an ideal day. Workplace health trackers can identify women who might be trying to get pregnant, help employers filter out workers with chronic diseases or those at higher risk of developing certain illnesses.

Algorithms can also reinscribe discriminatory practices in the delivery of public services. An algorithm in the US, for example, allocated health funding for Covid-19 based on previous health expenditure, meaning black patients typically received less funding despite being at higher risk. Algorithms that profile suspects of crime, and those that process credit or job applications, have been revealed to be similarly discriminatory.

Overall, unions in the region need new strategies – whether they be greater web presence to amplify their message, more international alliances to meet the deficit of weak union structures, or intelligent incorporation of technology that will enable workers to adapt to a new reality and guard against labor fraud. The union challenges in the region are multiple and complex, but without a doubt, transnational unity is the most powerful tool available to them.

If workers and their unions don’t have access to algorithms, it’s almost impossible to prove discrimination. If workers can’t access information on how decisions regarding their civic life, their right to access services and social protections are being determined, the entire notion of accountable governance stands discarded. Unions have long fought for transparent mechanisms to set wages and work conditions. But the secrecy that Big Tech now enjoys poses a huge challenge to unions working to eliminate discrimination. How are trade unions in Latin America resisting such incursions, Sofía?

SS: It is almost impossible to generalize the situation of the trade unions in the region. There are countries with strong union structures, as in Uruguay, Brazil, or Argentina, and weak ones, such as in Peru or Colombia. However, what is common to all countries in the region is that the introduction of technology in the workplace has made employment more precarious. The original fear of being displaced by a robot has now been replaced by the spectre of more precarious jobs, and the lack of rights and regulatory oversight. In some countries like Argentina or Uruguay, new laws regarding the right of teleworkers and platform workers to disconnect are being discussed and approved. In Argentina, they are discussing a law that will give trade unions the power to know the criteria applied when determining the source code of the algorithm to manage platform workers. Training of workers is becoming a key issue throughout the region and in all sectors. In this, trade unions have much to contribute.

Overall, unions in the region need new strategies – whether they be greater web presence to amplify their message, more international alliances to meet the deficit of weak union structures, or intelligent incorporation of technology that will enable workers to adapt to a new reality and guard against labor fraud. The union challenges in the region are multiple and complex, but without a doubt, transnational unity is the most powerful tool available to them.

KL: The lack of homogeneity is also true for the Asia Pacific. The issues facing trade unions are extraordinarily varied and often so huge that they can feel insurmountable. With close to two-thirds of the world’s population, the region includes both high income and least developed countries, countries with relatively strong trade unions and others where independent trade unionism is impossible. Trade unions usually have paid staff only in the higher income countries.

The trade union movement needs an ambitious agenda for the future, one that does not just restore, but also reimagines, the social contract. We need a democratic new deal – one that includes the proposals for a digital new deal and a green new deal.

The annual index of the ITUC found that workers’ rights are deteriorating faster in the Asia Pacific region than anywhere else. This means that trade unions in the region spend most of their time and energy on simply trying to survive, warding off attacks on trade union rights and members, and bargaining for improved conditions. This means they can rarely engage in research, policy work, or long-term strategizing. When the ‘future of work’ agenda is presented to unions, most think about short-term issues like job losses fueled by technological changes. These are legitimate concerns, but can lead unions to focus only on training and transitioning workers at the expense of the bigger picture. A number of union leaders can see, for example, the dangers of trade rules that cement the power of Big Tech, but it’s not easy for them to lobby for alternatives.

Our challenge, as global union federations, is to support unions and make them realize that this is a joint struggle – platform delivery workers and public sector workers impacted by ‘efficiency measures’ are bound together as workers but also bound together with communities and users of public services. The trade union movement needs an ambitious agenda for the future, one that does not just restore, but also reimagines, the social contract. We need a democratic new deal – one that includes the proposals for a digital new deal and a green new deal.

SS: What you say is so important, Kate! We have to include trade unions and civil society in the reconstruction of institutions that can lead to a better world. We need a new social contract and its architecture has to be tripartite – determined by the state, corporations, but most importantly, the unions. We cannot continue with digital models developed unilaterally by the state, as in China, or corporations, as in the US. The state is important, but you also have to be careful about authoritarian states. Either way, it can be the main promoter of a new world that includes all three constituents. What are your own views on the role of the state in this?

KL: One of the challenges we face is that workers and communities have become deeply cynical about the state and are often more worried about governments’ access to data rather than corporations.

Besides, the line between the state and Big Tech is getting increasingly blurred. Big Tech has not just sought to provide services on behalf of the state, but often to displace it altogether. Smart cities, for example, have been designed to function as private cities, collecting data from every interaction. India plans to build 100 smart cities, the most famous of which is the city of Gurgaon. All services, including emergency services, street repairs, water, and energy are privatized and digitalized. But while Gurgaon boasts state-of-the-art buildings and houses, workers employed to run these services live in its many slums without access to water and sewage systems, amidst uncleared garbage and roads full of potholes.

The influence of Big Tech is so great that governments are often too intimidated to regulate or criticize them. An Australian federal government employee published a journal article which pointed out how these companies were amongst the very few profiting during the Covid-19 pandemic. The department management alleged the article was a breach of the public service code of conduct that prohibits public employees from publicly criticizing the government. The policy, the management alleged, extended to current or potential future public-private partnerships with Big Tech. The worker was forced to resign.

Nevertheless, the role of the state, of democratic governance, is vital to envision data as a public good. Our aim should be to restore effective governance and develop public sector architectures capable of governing the use of our collective data. We need to do more to consider options for public data governance. If e-commerce is good for local providers, why not have a public platform that doesn’t mine the data for its own monopolistic purposes? Why not have public cloud space so that public data can be kept securely without potentially being mined? If digital health diagnostics is indeed beneficial, why not make it a part of the public health system so that the metadata can help design better public health responses?

Much of the technology that Big Tech relies on was developed by the public sector. Yet, the profits and the benefits of that technology have accrued mainly to the obscenely rich. Only a democratic state response can change that. I’d be interested to know the Latin American experience in this regard, Sofía?

SS: The role of the state in Latin America is difficult to analyze, given the current political situation. In most countries, far-right governments are pushing for digital colonialism rather than digital industrialization. Most of them are not amenable to labor rights or putting limits on transnational companies. The exceptions are Argentina, Venezuela (a very controversial case), Mexico, and now we regain hope with Bolivia. In the midst of a pandemic and despite a shattered economy, Argentina introduced a cutting-edge legislation that grants workers engaged in telework the same rights as face-to-face workers. The legislation includes the right to disconnect and weaves in a gender perspective by allowing the reconciliation of working hours with care responsibilities.

The state is, without question, a fundamental actor in the defense of labor rights. But when it is absent, trade unionism is workers’ only hope. The resistance in the region is remarkable. Trade unions in various countries are primarily responsible for resisting the attack of neoliberalism and ushering in labor reforms, even as governments try to push for adjustment policies to be paid for by workers. In Uruguay, for instance, the pandemic is being used as an excuse to promote labor laws that will ‘flexibilize’ the market and take away social benefits that were gained in the last decade. In Brazil, Peru, and Colombia the situation is even worse and workers have to decide whether to stay at home and lose their jobs or go to work and get sick. There is no social protection or unemployment insurance.

All these measures are promoted by the US government and corporations. On Twitter, Elon Musk said about Bolivia, “We will coup whoever we want.” Governments in the region are financed and propped up by the US to maintain dominance over the region, promote their technologies, and push back against China. Another example of this was the recent election of the president of the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB). Historically headed by a Latin American, it is now led by a North American, Mauricio Claver-Carone, for the first time in history. In his first speech, he said he will actively work to kick China out of the region. Governments and Big Tech interests are connected together in ways never imagined. You mentioned the blurring lines between the state and Big Tech, Kate. In what ways are unions engaging with international rules that cement the power of data companies?

KL: Unions have played a leading role in campaigns against unfair trade rules at the WTO and in trade agreements. But these struggles have primarily focused on the impact of tariff reductions and rules that make national industries and local jobs less viable. We have worked with affiliates to understand the broader dangers of trade rules: services chapters that turn public services into commodities and promote privatization, intellectual property rights that make medicines unaffordable, and the power accorded to corporations to sue governments for laws or practices that undermine their capacity to make money.

But the e-commerce trade rules included in the rather Orwellian Comprehensive and Progressive Trans Pacific Partnership Agreement were a new challenge. Since the agreement was signed and released, we’ve worked with affiliates to understand how the rules give even greater powers to Big Tech – source code is protected and governments cannot demand that it be made available to the public, or even to the government, governments cannot require source code to be stored locally, corporates cannot be required to have a local presence, e-commerce transactions cannot be subject to tariffs. We have analyzed how the e-commerce chapter impacts health, local government, and energy workers.

The problem remains that this is one of many, many challenges facing unions. The best way to campaign on these rules is to show that they are all part of the bigger threat facing unions – unbridled corporate power. Of course, the form that our campaigns and activism take have to be reimagined in the post-Covid world. The pandemic has forced us to think more about digital activism. In general, there is a renewed emphasis on cyberactivism within the union movement as people increasingly turn to varied forms of social media for information. Would you agree Sofía?

SS: Absolutely! I also think that recent experiences of cyberactivism by TikTok users in general, and K-pop fans in particular, has important lessons for trade unions. A generation of teenagers are outwitting algorithms to make their voices heard. More recently, they even managed to affect the turnout at the US president’s campaign. This mode of activism is remarkable because these teens understand how to take coordinated action and achieve concrete results. And to achieve this, they deploy technologically very strategically.

I think trade unions should take a leaf out of this book. They need to pay attention to the causes that move the younger generation of workers and incorporate them into their demands. This is critical to mobilize a generation of young workers who are not only concerned about job insecurity but also about leaving their fingerprints on the web. That said, unions have been engaging in cyberactivism well before the pandemic, with some very positive results.

KL: I think cyberactivism is critical to foster international solidarity, particularly if there’s a sensitive global brand in the picture. A great example is the campaign led by the Kodaikanal Workers’ Association to secure justice for workers suffering from mercury poisoning caused by a Unilever-owned thermometer factory in Tamil Nadu, India. Unilever ignored them for 15 years until they partnered with the Vettiver Collective and a young woman rapper Sofia Ashraf produced the song ‘Kodaikanal Won’t’ that went viral and forced Unilever into a settlement with the workers. Of course, there are many constraints. Few unions have widespread access to the technologies and skills that a well-developed digital strategy needs. Language differences across the region are always a challenge. And so, online activism always has to work in tandem with other forms of trade union responses.

SS: Certainly, cyberactivism has to be one more tool in the social struggle. It is necessary to understand how it works and incorporate it into current union strategies. But at the same time, the traditional forms of union organization must continue. Technology brings new ways of communicating but empathy and community are irreplaceable. The first trade unionists of the post-industrial era ‘walked the factories’ to get more members, and greater union representation is still the main force. The factory, the workplace has now changed. The new generation of union delegates are not only present on social media networks, but are willing to go further and visit workers at home when they allow it.

It is also essential to have meeting places in the union premises to foster a sense of fellowship. A sports day, a picnic, a training workshop, a talk in the afternoon – these small steps will ensure that workers in general, including teleworkers and those who have had to develop new modes of working as a result of the pandemic, manage to find ways to connect, so that working in isolation does not become a barrier to union organization. In your own work Kate, what other ways are you using to respond to the current crisis?

KL: Right now, I think we need to reimagine our social, economic and political lives. If we start by acknowledging that our societies should be organized around the capacity to care and stand in solidarity with all, and that the point of digital data should be to aid that process, we can develop new proposals for governing data, societies, and work. At PSI, we are trying to find ways to build union knowledge on issues relating to data governance, identify advocacy opportunities, and shape possible government responses. At the same time, we are working on issues like corporate tax avoidance, particularly by Big Tech. We hope unions can help campaign for digital profit taxes as a step toward global tax reforms. Finally, we want to emphasize the ideas of data as a public good and data commons. We have to start by introducing producer rights over data – if workers produce data, they have a right to the benefits that accrue from that data. In the same way that unions have negotiated copyright entitlements for journalists, we have to campaign for data ownership rights to sit with the producer of the data and be licensed for use only where appropriate.

These changes won’t happen overnight. But building strong, well-organized alliances between workers and unions across countries and sectors is a necessary first step. In the last 40 years, corporations have secured rights to move capital freely across borders while prohibiting cross-border solidarity. They have fed us the convenient fiction that subsidiaries are separate entities. This is not just a strategy to escape taxes and accountability but also thwart workers’ efforts to organize.

We have to start by introducing producer rights over data – if workers produce data, they have a right to the benefits that accrue from that data. In the same way that unions have negotiated copyright entitlements for journalists, we have to campaign for data ownership rights to sit with the producer of the data and be licensed for use only where appropriate.

Despite such unbridled corporate power, it is now possible to imagine a global strike of Amazon workers, for example. Polish Amazon workers went on strike in solidarity with German Amazon workers earlier this year. It would be even better if, along with these strikes, we could imagine global solidarity actions that demand structural change. What other strategies, alliances, and labor rights do you think need to be achieved in the present context, Sofía?

SS: I think the union movement is definitely getting stronger with new alliances. Going forward, we need to think about joint struggles not only between unions within the same sector, but also across sectors as production processes become more interlinked. As I mentioned earlier, there is a strong lobby in the WTO that sees each part of a production process as a service. With the advancement of the digital economy and internet of things, everything is potentially a digital service, with strong linkages between sectors. In the commerce sector, for example, a strong alliance between the banking and logistics sectors is unavoidable thanks to e-commerce. This makes multisectoral alliances on the part of unions an imperative.

The right to disconnect was conceived as a new right not only in the interest of workers’ mental health but also as a powerful tool for gender equality. It is the right of every worker not to be contacted outside of working hours by their employer. This not only allows you to enjoy your free time, give your mind a rest from daily tasks, but also helps you regain sovereignty over time so that families can better distribute household chores. Being contacted after work hours should be seen as a lack of respect for the worker. In Argentina, we successfully pushed for teleworkers’ right to disconnect but it needs to be extended to every worker in the country, and throughout the region.

Finally, we also need to limit what information companies can collect on their workers and what they can do with it. Workplaces must seek express and prior consent from workers before collecting such data. Workers need to be aware of what information is being circulated about them and they must have the opportunity to request that this information be eliminated once the employment relationship ends.

I really do not see much awareness among unions in Latin American about the implications of mass surveillance. Workers are subjected to surveillance through facial recognition systems, specific softwares installed on their computers, ‘intelligent buildings’ which have sensors and cameras everywhere. The general population seems to be asking for more surveillance to cope with crime in large cities, an ‘I-have-nothing-to-hide’ attitude prevails in workplaces, and unions are not yet aware of the dangers of the constant monitoring by companies and governments. And ironically, trade unions themselves are at the risk of being surveilled and persecuted through these technologies. The resurgence of far-right governments, as in Brazil, suggests that if more such governments come to power in the future, with surveillance technologies already installed, social movements will face their worst fight. So it is worrying to see that social movements do not take this demand as a direct attack on democracy and freedom.

KL: As grim as that is, do you think there is ‘hope’ for the social movements in general, and the trade union movement in particular?

SS: There’s always hope. That is never lost. Trade union movements in the Americas have survived military dictatorships and plans to dismantle governments. They have always come out of these disruptions renewed and strengthened. The region’s tradition of struggle, protest, and solidarity are an invaluable asset.

The solidarity that social movements across Latin America have demonstrated is remarkable. The feminist movement in particular spread like wildfire and there is a strong sense of sisterhood, especially among the youth, who are no longer willing to tolerate patriarchal outrage.

Trade union movements in the Americas have survived military dictatorships and plans to dismantle governments. They have always come out of these disruptions renewed and strengthened. The region’s tradition of struggle, protest, and solidarity are an invaluable asset.

The trade union movement thrives on these struggles in the region. Political resistance creates a common enemy. Resisting neoliberalism and neoimperialist attacks from the US has helped us join forces against a common cause and achieve a united Latin America.

Hope for the future lies in the region learning from young people. With the strength of the institutional framework that it has created over the years, these lessons can transform Latin America into a new sovereign digital economy, with rights for all workers.

KL: Yes, I agree, there’s always hope. The pandemic has exposed the deep flaws in the current economic and political order. But it has also brought about a renewed respect for public services and the workers who deliver them. This has perhaps opened up a space for discussions about the risks of precarious work and privatized services and potential alternatives.

But it’s really important that we also recognize that corporations see all crises as opportunities for profitmaking and influencing policy. Big Tech has made the greatest gains in the pandemic – what Naomi Klein has called the Screen New Deal.

Trade unions represent the largest democratic membership movement in the world. We can point to many wins. We know that trade unionism delivers better wages, better societies, and greater equality. We know that power cannot be shifted without a fight. We know that Big Tech companies have amassed so much profit that their wealth dwarfs most government budgets. Yet, I am hopeful every time I look at other historical movements that sprung up against capital amassed by a tiny few and delivered unprecedented changes for the benefit of all.

Kate Lappin is the Asia Pacific Regional Secretary for Public Services International – the Global Union Federation that represents 30 million workers and their unions who deliver public services in more than 150 countries.

Sofía Scasserra is an economist, has a Master’s in international relations, and is currently a PhD candidate in epistemology. She is an advisor to the global presidency of UNI Global Union and the Argentine Senate. She is also a professor and researcher at the Julio Godio World of Work Institute of the National University of Tres de Febrero.