Foreword: A Digital New Deal as if People and Planet Matter

The Digital New Deal Team

One of the first undertakings in what one might call ‘Big Data’ in fact began with a progressive political agenda far removed from the proverbial garages of Silicon Valley. In Chile, in the early 1970s, Salvador Allende, the first Marxist leader to be democratically elected as head of state, assembled a motley crew of economists, cyberneticians, and engineers to embark on Project Cybersyn, an ambitious attempt to build a center of intelligence for the national economy. Equipped with hundreds of telex machines that would feed in data in real time from factories and other productive outlets, the project was envisioned to maximize efficiency, cut out waste, and respond dynamically to various crises. It was an attempt to harness technology towards a socialist mode of governance.

But Allende was violently ousted from power through a military coup in 1973, ushering in the brutal, 17-year dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet. Under Pinochet, Chile would go on to become the first laboratory of neoliberal reforms that supplanted the Keynesian/New Deal consensus of the post-war years.

Looking back today, it is striking to note the prescience of Project Cybersyn. Much of what it boldly imagined has come to pass, albeit in a form and with a political content diametrically opposed to its original vision. We cannot deny the central role that data and digital technology play in our everyday lives and the manner in which our societies and economies are increasingly being restructured. At the same time, however, the levers of these technologies have almost entirely been usurped by large transnational corporations and the profit imperative.

Over the past decade, digital enclosures and data greed have consistently blunted the power of the internet and data-based intelligence as an emancipatory force. The platform economy is dismantling and reorganizing systems in their entirety – from communication, media, and transportation to commerce, agriculture, finance, and governance – hollowing out social and public value and ushering in a marketization of everything.

The Covid-19 pandemic has further accelerated the tendencies of digital capitalism to swallow whole the resources of this planet and its people, starkly visibilizing the underlying inequality and injustice of the global economic paradigm. Big Tech giants have resorted to unabashed opportunism during the pandemic, consolidating their market dominance, placing themselves at the center of trade and logistics, and moving swiftly to displace public interventions in the provisioning of key social services. They have not been alone in leveraging digital technologies towards greater power and influence. Nation states have used sanction-by-pandemic as a way to expand authoritarian power, adopting more and more measures to track and surveil populations – measures that without safeguards and sunset clauses could easily weave into the governmentality of statecraft, shrinking room for dissent.

We should not make the mistake of interpreting the fallouts of the Covid crisis as exceptions to an otherwise robust system. The digital opportunism that has nimbly followed the crisis is not a signifier of positive disruption. Rather, it is a sign that the techno-economic paradigm rooted in a neoliberal trajectory is deepening the system’s exclusionary, extractive, and exploitative outcomes.

Social actors concerned with a just and equitable society have called attention to the urgency confronting us at this moment to reshape the global economic and development order. A digital paradigm – one that unleashes equality, solidarity, sustainability, and justice – is only possible through an overhaul of existing institutions. The digital needs to be reclaimed, and towards this, the purpose and meaning of the internet, and data-based intelligence, must be rearticulated. The institutional frames and global-to-local governance mechanisms of data and digital infrastructures (including platforms and standards) comprise the lynchpin in the battleground between democratic futures for all and private profits for the few. These frames need to be clearly spelled out so that the forces of transformative change can evolve a concerted critique and coordinated action.

As a step towards this, the Digital New Deal compendium brings together leading thinkers, activists, and practitioners from across the globe. The contributions offer an incisive diagnostics of our current predicament, outlining the new challenges for food sovereignty, labor rights, climate justice, and equitable development. They critique the discursive and institutional underpinnings of the internet, data, and AI technologies that have disenfranchised communities and people. Beyond calling out what ails the world, our authors also set for themselves the challenge of imagining new possibilities to reclaim the digital for justice. The essays in this collection are thus bold leaps of imagination with intimations from an alternative present – all relating to a digital world that is still within reach, and which, we believe, is worth fighting for.

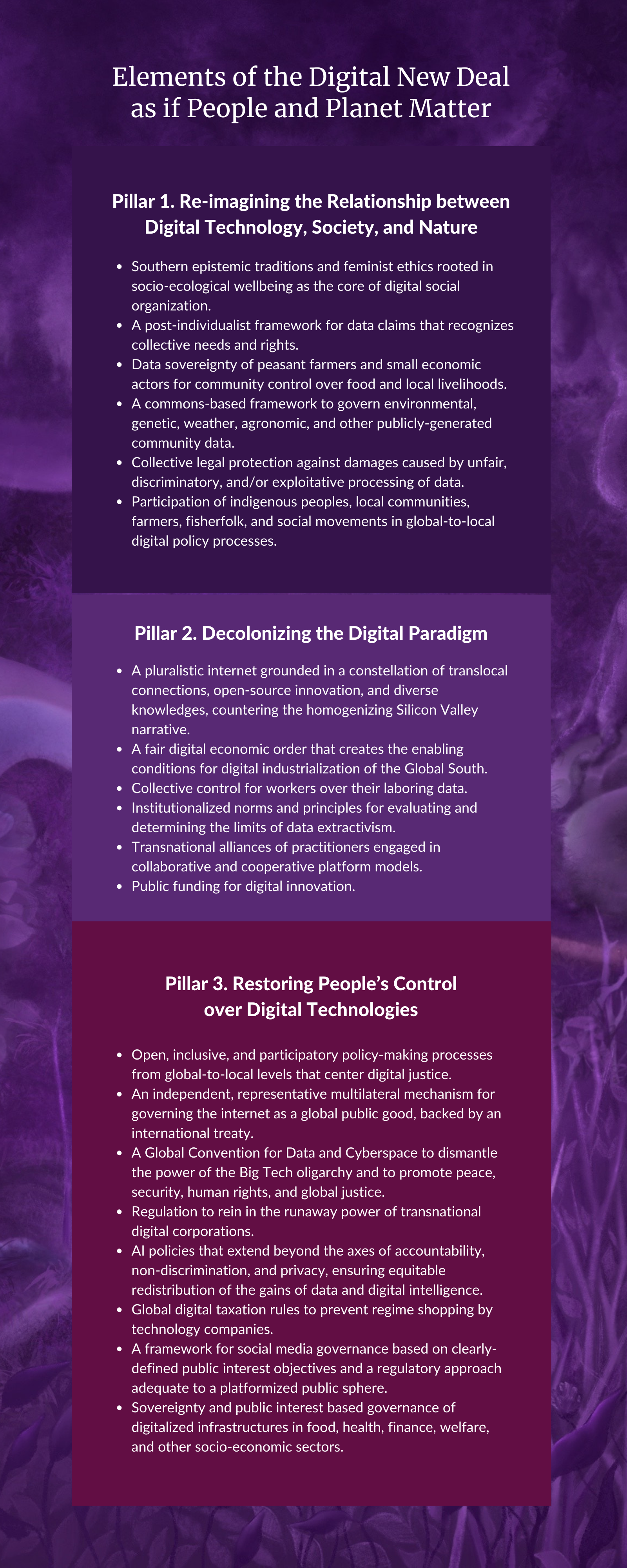

We discuss below the various threads emerging from the essays, pulling together the elements of a digital new deal.

Taking back power from Big Tech

Several essays track and problematize the growing ways in which digital technology has, in essence, become a part of our social and public infrastructures. In their essay, Gianluca Iazzolino, Marion Ouma, and Laura Mann invoke the concept of ‘functional sovereignty’ to denote the way platform firms are able to dictate the terms and conditions of the market, siphoning off value from the activity of others. Going forward, the massive data resources that they control will make it possible for these tech giants to shape scientific evidence, thereby granting them the power to influence the trajectory of our collective knowledge production.

In the aftermath of the pandemic, we already see an acceleration of Big Tech’s presence in key sectors of the economy. As the ETC Group argues, food production and distribution are becoming an important sector for huge investments from large tech firms like Amazon and Alibaba as well as traditional firms like Bayer-Monsanto. Concepts like ‘precision agriculture’ that are rapidly gaining currency denote business models where huge swathes of data are collated from across the production process, and used to reorganize the manner in which food production happens. These disruptions are likely to place huge burdens on farmers, peasants, and those in allied industries, especially in the Global South, threatening their livelihoods and the food sovereignty of nations.

The autonomy and wellbeing of all communities and nations therefore urgently require new norms and rules for the platform economy, including a commons-based data governance framework that puts the control over their data back in the hands of communities.

Democratic governance of the internet and digital technologies

A common refrain across the essays is the urgent need to end the neoliberal consensus that has legitimized an ever-expanding role for the private sector in digital governance and policy processes. The Digital New Deal advocates for democratic governance and effective regulatory mechanisms across the digital domain, placing people-centered development at the core.

To this end, the compendium offers both principles as well as concrete proposals in the domains of data governance and sovereignty (Roberto Bissio and Richard Hill), public sphere and social media (Amber Sinha), AI governance and systems design (Jun-E Tan and Amba Kak), digital labor (Christina Colclough, Kate Lappin and Sofía Scasserra), data justice (Maui Hudson, Mariana Valente and Nathalie Fragoso, Emiliano Treré and Stefania Milan) and international e-commerce (Richard Kozul-Wright). In each case, there is an emphasis on creating mechanisms that will monitor the development trajectory of digital technologies across all sectors of the economy, and mitigate the monopolistic concentration of power that Big Tech currently enjoys.

Many essays underline the role of state policy as a crucial instrument for breaking the data enclosures of large transnational companies. Governments must be able to harness data as an economic resource in order to facilitate an inclusive development strategy in their respective nations and claim a public role for technology. Here, the authors of the Digital New Deal do accede that the nation state is often captured by private interests and is capable of the worst abuses of citizen data. Therefore, as Roberto Bissio and Richard Hill argue in their essays, democratic digital futures hinge on a global effort to negotiate a new digital paradigm through new global norms and institutional arrangements. Also, genuine progress towards global economic justice is not possible unless the de facto dogma of ‘free data flows’ can be countered with an international normative framework that recognizes the rights of all nations and peoples to the data they need for charting their development pathways.

Rebuilding the public sphere

The compendium touches on issues related to the legal quagmire within which social media regulation currently rests – specifically, the challenges around creating effective mechanisms to curb the misinformation, hate speech, and growing polarization resulting from algorithmically generated echo-chambers.

As Amber Sinha argues in his essay, while free speech is important to safeguard, it is increasingly clear that analog imaginations to regulate platforms are inadequate for appropriate regulatory scaffolding. Similarly, Anita Gurumurthy and Nandini Chami point out a glaring normalization of sexism and misogyny in design architectures of the online publics, which calls for a new theoretical basis for progressive action.

New political frameworks and actions

Alongside efforts advocating for a more just local-to-global governance regime in the digital domain, essays in the compendium also stress other key initiatives – building novel institutions and new alliances, as well as rethinking some of our key concepts and theoretical frameworks.

Christina Colclough, in her essay, puts forth the idea of ‘workers’ data collectives’ that can function as a representative body in negotiating and managing the interests and data of workers in a particular sector. Other pieces also talk about alternative, bottom-up practices that attempt to use digital technology in innovative ways – from apps using co-operative business models to open-source communities and digital toolkits that have enabled workers from different parts of the world to come together and collaborate.

Through theories of post-humanism as well as indigenous epistemologies, contributions by François Soulard, Maui Hudson, Azar Causevic and Anasuya Sengupta, Anita Gurumurthy and Nandini Chami persuade a rethinking of the relationships between the digital paradigm and the increasing precarity of our natural environment, arguing for a transformed subjectivity, new vocabulary, and radically different approaches to make sense of and reclaim the digital phenomenon.

Pandemic as a turning point

Capturing the discontinuities in a post-Covid global order, the essays in this compendium stress the urgency for new thinking and action. The hope, as always, lies in the power and energy that social movements bring, dismantling the status quo, paving the way for equity and justice, and offering the power to dream.

The Digital New Deal Team

January 2021