Latin American Visions for a Digital New Deal: Towards Buen Vivir with Data

Stefania Milan & Emiliano Treré

para Diego Armando Maradona, desde los márgenes a las estrellas

[for Diego Armando Maradona, from the margins to the stars]

In this contribution, we explore the notion of ‘data poverty’ to examine the social costs of the first pandemic of the datafied society and identify critical fault lines in the dominant digital paradigm. We engage with Latin American perspectives and traditions, especially in the fields of popular education and communication for social change, to outline three key elements of a Digital New Deal: critical ecology, liberation pedagogy, and autonomous design. Taken together, we argue, these components can intercept and mitigate the new forms of data poverty visibilized and exacerbated by the pandemic. Subsequently, we mobilize the Andean indigenous social philosophy of buen vivir which outlines “a way of doing things that is community-centric, ecologically-balanced, and culturally-sensitive”. We elucidate the three ingredients of a ‘buen vivir with data’, namely the fusion of the social with the ecological question, a dialogic and participatory approach to decision-making, and a “localized, relationship-oriented” practice of community care and solidarity based on the recognition of ontological difference and commonalities. We conclude by illustrating how the notion of buen vivir can help us understand the present and collaboratively design a better future for the digital realm and beyond.

Introduction

In the second decade of the 2000s, cities are smart, service work takes place through platforms, society is datafied, and our lives are increasingly quantified and monitored through an array of dashboards and biometric technologies. The world has never been as technologically advanced as it is today. Yet, an infinitesimally small virus was all it took to bring the world to a grinding halt. Economic, educational, and social activities have been paused while the vaccine is rolled out. Friendships, family support, and work have been displaced to the digital sphere. Not only has the Covid-19 pandemic unveiled our fragility in the face of a global health emergency, it has also exposed our dependence on digital infrastructures for a myriad of crucial activities – from remote working to service delivery, from medical care to the monitoring of public space. It has massively accelerated the digital transformation of sectors as diverse as public education and public administration. The magnitude of this global health crisis seems to have prevented us from taking a critical view of the dominant digital paradigm but the time is ripe to re-evaluate the techno-architecture of the present and decide what the digital society of the near future should look like.

Not only has the Covid-19 pandemic unveiled our fragility in the face of a global health emergency, it has also exposed our dependence on digital infrastructures for a myriad of crucial activities.

The New World Information and Communication Order (NWICO), which at the turn of the 1980s was the first multilateral debate to put cultural imperialism on the global agenda, is now only a faint memory. Yet, the scale of the current crisis calls for a rethink of the prevailing social and economic order in ways that are commensurate with justice, equality, and environmental sustainability. In this essay, we review the social costs of the first pandemic of the datafied society to identify critical fault lines of the dominant digital paradigm. We then learn from Latin American traditions and perspectives, especially in the fields of popular education and communication for social change, to sketch out three core elements of a Digital New Deal: critical ecology, liberation pedagogy, and autonomous design. Taken together, these components can intercept and mitigate the new forms of data poverty visibilized and exacerbated by the pandemic. In the concluding section, we mobilize the power of the Andean indigenous social philosophy known as buen vivir – “a way of doing things that is community-centric, ecologically-balanced and culturally-sensitive”. We delineate the three ingredients of a buen vivir with data and illustrate how it can help us understand the present and collaboratively design a better future for the digital realm and beyond.

After the digital divide: Data poverty in the time of Covid-19

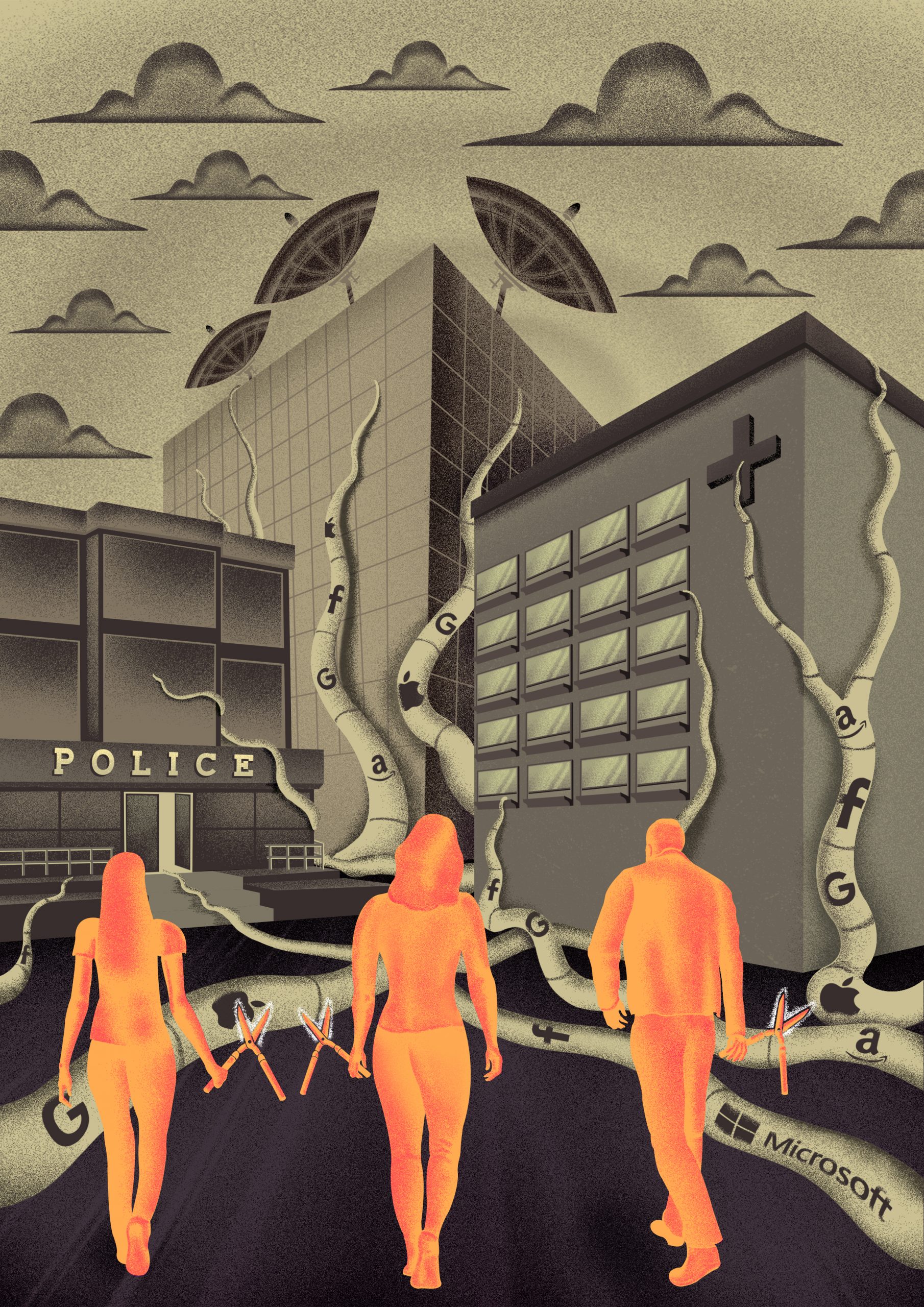

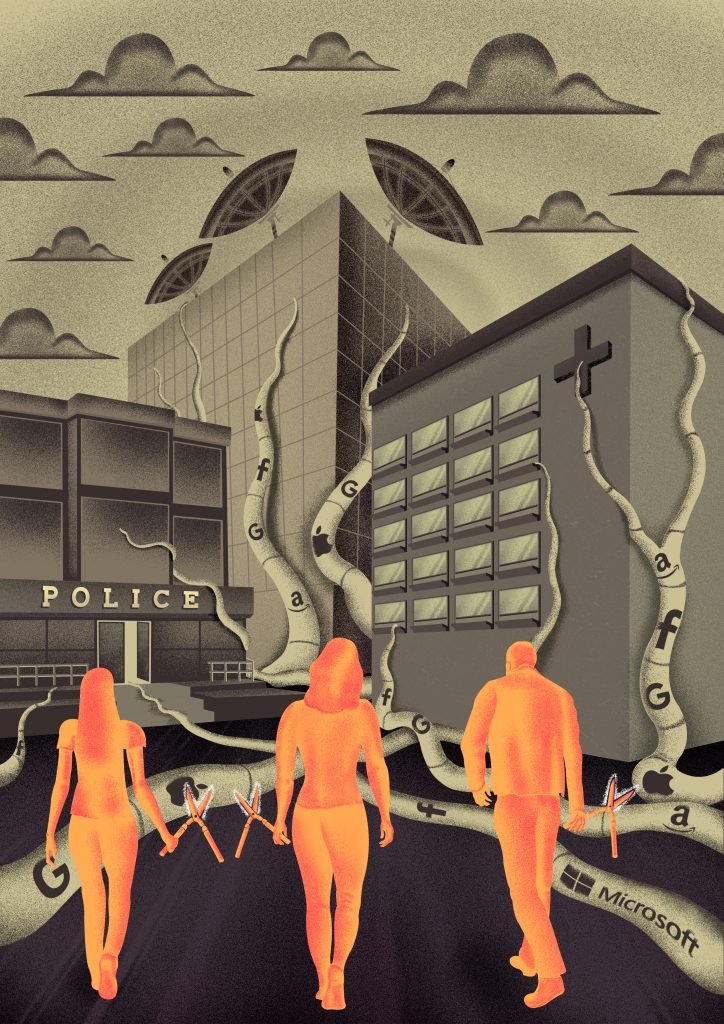

The pandemic has upended established ways of doing things, from shopping to traveling, from leisure to learning. It has made a handful of wealthy technology companies even richer, strengthening their quasi monopoly in sectors like e-commerce, cloud computing, and content streaming. Amazon, for instance, has doubled its profit during the pandemic while revenues of Microsoft’s Azure has increased by 48 percent, buoyed by the sales of cloud computing services. Even before the pandemic, state sovereignty had been jeopardized as strategic infrastructures such as healthcare data or border control technology moved into private hands. This trend has only expanded in the aftermath of Covid-19. Tech solutions such as location tracking have allowed us to perform remotely activities that would otherwise require co-presence such as university exams or office work, while legitimizing large-scale data surveillance with no end in sight. “Largely without public debate – and absent any new safeguards,” warned Ronald J. Deibert, author of Reset: Reclaiming the Internet for Civil Society (2020), “we’ve become even more dependent on a technological ecosystem that is notoriously insecure, poorly regulated, highly invasive and prone to serial abuse.”

This has also left huge sections of the world’s population stranded and alienated. In our increasingly digitized and privatized world, only 53 percent of the population has some form of access to the internet, reports the International Telecommunication Union. The digital divide might no longer be high on the list of concerns for policymakers and multilateral organizations, supplanted by the dazzling marketing of tech companies and their efforts in the “zero rating” department, but it is by no means a problem of the past. On the contrary, it is worsened by the new class of advanced skills that are necessary to thrive in the datafied society, including data literacy, basic statistical knowledge, and perhaps even the ability to interpret code. Furthermore, it is now exacerbated by the impossibility of digital disconnection. The Covid-19 crisis has demonstrated that the choice to not be connected to digital networks and apps constitutes a privilege that many citizens cannot afford. For many workers whose livelihoods depend on the decisions taken by the algorithms of digital apps, there is no possible break from the data deluge and the sheer intensity of permanent, coerced connection.1

For many workers whose livelihoods depend on the decisions taken by the algorithms of digital apps, there is no possible break from the data deluge and the sheer intensity of permanent, coerced connection.

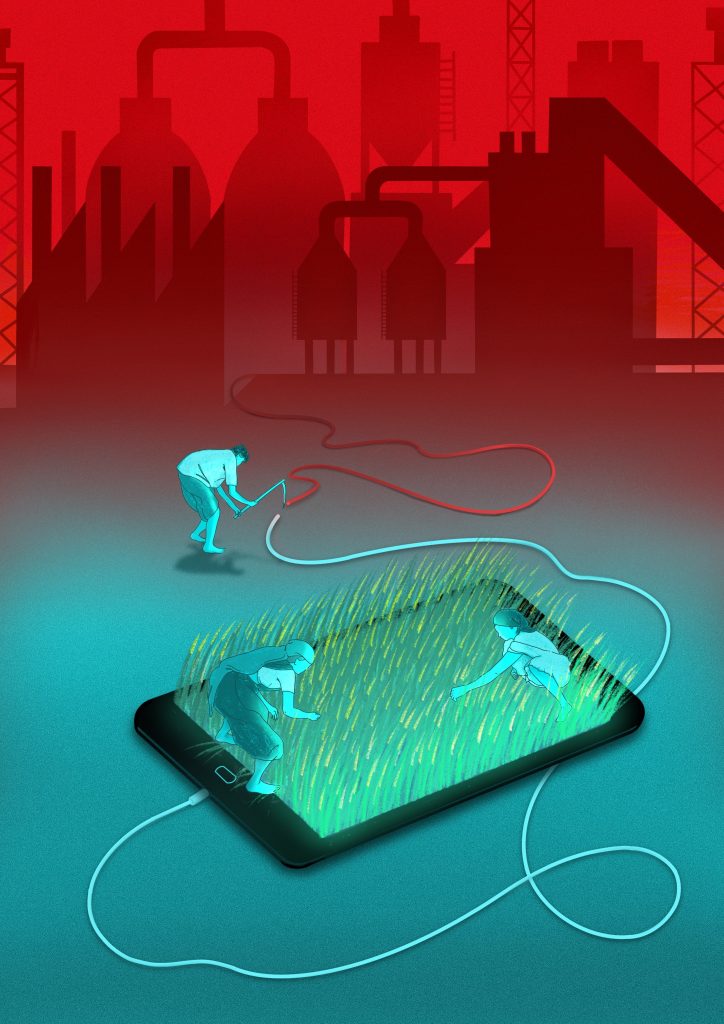

The pandemic has laid bare our over-reliance on quantification as a way to know and act upon the virus, with data becoming “a sine qua non condition of existence”.2 At the same time, it has exposed the weaknesses inherent in a number of technological solutions which were once presented as innovative ways to tackle societal inequalities. Biometric welfare in India may have made people go hungry when the risk of disease transmission associated with users’ fingerprints interrupted the distribution of food rations to impoverished families. The reach of citizen-scoring mechanisms based on automated detection of pockets of poverty, like the Colombian System of Possible Beneficiaries of Social Programs (Sisbén), have been extended by Covid-19, but the opacity and contradictions of their faulty algorithms have also been exacerbated. The design of these systems makes it virtually impossible for citizens to reclaim their social rights – let alone have a say in the decision-making process or correct algorithmic errors. Elsewhere in Latin America, distance education has exposed the limitations of a one-size-fits-all solution for rural areas. In Peru, for instance, governmental response to the pandemic glossed over the many socio-technical divides that still affect the country, leaving behind many families with no internet, TV, or radio access. Finally, the pandemic aggravated the already harsh working conditions of gig and delivery workers in both developing and wealthy countries, enslaved to the platform, forcing them to take on extended working hours in risky, unsafe environments, chasing the whims of algorithms.

We can file these distortions of the prevailing techno-solutionism under the rubric of data poverty. As we argued elsewhere, data poverty concerns a multifaceted condition of invisibility that becomes particularly dangerous during a pandemic. It has little to do with data exploitation3 or data colonialism4 which might come across as “luxury problems” in the face of a soaring Covid-19 death toll (which stood at an appalling 1.4 million at the time of writing). Rather, as “data is tied to peoples’ visibility, survival, and care”, the pandemic has revealed two types of data poverty. The first has to do with the scarce statistical and testing capabilities of developing countries. The second concerns a growing number of invisible populations within distinct geopolitical and socio-political contexts – including gig workers, sex workers, and undocumented migrants. While these segments of society suffer invisibility in ordinary times as well, during the pandemic their condition is particularly challenging; being invisible to the state might engender more risks and threats for these populations and their surrounding networks and communities. Furthermore, it can lead to exclusion from subsidies and welfare support – or even basic forms of assistance such as healthcare – even within resource-rich nations.

While data poverty maps into existing inequalities and exacerbates them, it also corresponds to a more general loss of agency for the individual and the community over their well-being. The forms of invisibility it perpetuates can deprive entire populations of voice and sovereignty over their futures. In this respect, investigating the impact of data poverty might help us to situate one of the paradoxes that has defined the governmental response to the Covid-19 crisis. On the one hand, governments across the globe have relied extensively on technocratic know-how, “expert committees”, and ad hoc “task forces” operating outside the control and constraints of democratic accountability. This approach has resulted in the imposition of top-down measures, stripping local communities of the power to define what constitutes community and care during a global pandemic. At the same time, individuals who have no control over this decision-making have frequently been penalized for not adhering to oftentimes draconian rules and dispositions such as lockdowns, their inability to do so framed as “recklessness” and blamed as the key factor in the aggravation of the pandemic. For all these reasons, we argue that rehabilitating the agency of individuals and their communities should be at the core of a Digital New Deal oriented toward destabilizing the dominant digital paradigm and offsetting the externalities of widespread data poverty.

Lessons from Latin American scholarship and movement praxis

We now turn our attention to Latin American scholarship and community practice in search for productive venues to address the problems of data poverty and the resulting loss of agency and sovereignty that go hand in hand with the tech industry’s rising power over public and private life. Latin America is one of the most unequal regions of the world and has suffered a disproportionate loss of lives in the wake of the pandemic. Yet, over past centuries, the region has also nurtured a one-of-a-kind grassroots activism and critical scholarly thinking “pushing the boundaries of what it means to pensar desde el Sur [think from the South]”.5 Three critical fields of scholarly intervention and movement praxis provide food for thought to support our effort to draw the outlines of a Digital New Deal: critical ecology, liberation pedagogy, and autonomous design. These interventions go beyond the exposure of systemic injustice with roots in colonialist exploitation, and offer productive venues for social change centered on the individual and the community.

Taken together, these three disruptive epistemic operations allow us to foreground the autonomy of individuals and communities vis-à-vis the industry and the state, which we argue, should be at the core of any Digital New Deal.

Critical ecology builds on the Latin American traditions of biodiversity and ecology preservation endorsed by eco-social movements like the Brazilian Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais sem Terra and the international peasants’ movement Vía Campesina. It can inspire a Digital New Deal for two reasons. Firstly, it firmly positions the ecological question at the center of the social question – since “In the South, the ‘social question’ and the ‘ecological question’ get meshed together”6 – and calls for “a necessary biocentric and bioethical turn”7 in our understanding of our tech-mediated social relations. It invites us to put on “ecological spectacles”8 to acquire a holistic vision “based on a new paradigm which has the Earth as its root and foundation”9. Secondly, it encourages us to reignite the debate on the dependency of much of the Global South on technology developed in the North. “The ecological perspective again opens the discussion about the relations of international dependency,” writes Joan Martinez-Alier in an article aptly titled Ecology of the Poor. The “North-South conflict can now be seen also as an ecological conflict.”10 In a nutshell, the critical ecology tradition interrogates societal over-reliance on technology that, contrary to market propaganda, is the poisonous fruit of twisted political economy histories and has a skyrocketing environmental footprint.

A second tradition of interest concerns liberation pedagogy, also known as pedagogy of autonomy. In the 1960s, Brazilian educator Paulo Freire, influenced by Marxism and liberation theology, criticized the inability of the education system to empower the dispossessed to overcome their condition. In response to this structural problem, Freire proposed an educational approach that centers human beings as active agents in transforming their world and is based on dialogue and horizontal relationships between learners and teachers. Acknowledging that theory and practice of social change should go hand in hand if they are to break the prevailing ‘culture of silence’, liberation pedagogy can nurture a “critical consciousness” (conscientização in Portuguese) seen as “an intrinsic part of cultural action for freedom”11 Liberation pedagogy is of value here for three main reasons. First, it attributes an active role to individuals and communities in shaping their futures. Second, it conceptualizes the unity of praxis (e.g., engagement with technology) and theory (e.g. values) in social change. Finally, it interrogates the paternalistic approach that has often characterized governmental response to the pandemic, evident in coercive measures like lockdowns.

Last but not least, “autonomous design” – a term coined by anthropologist Arturo Escobar – provides another useful lens to productively imagine our post-pandemic futures. It takes the lead from critiques of the development project (“a grand design gone sour”), and from the Zapatista12 cosmovisión (worldview) of the pluriverse, “a world where many worlds fit”. Escobar asks “how difference is effaced and normalized – and conversely, how it can be nourished.”13 Grounded in “an ethical and political practice of alterity that involves a deep concern for social justice, the radical equality of all beings, and nonhierarchy”, autonomous design argues that design (of technology, policies, society) “can be reoriented from its dependence on the marketplace toward creative experimentation with forms, concepts, territories, and materials, especially when appropriated by subaltern communities struggling to redefine their life projects in a mutually beneficial relationship with the Earth.”14 Bringing the pluriverse to the fore encourages us to make room for and give voice to ontological difference in the Digital New Deal – an approach that is diametrically opposed to the one-size-fits-all techno-solutionism15 of our pandemic reality and helps to overcome the “data universalism16 that have characterized many Covid-related solutions.

Taken together, these three disruptive epistemic operations allow us to foreground the autonomy of individuals and communities vis-à-vis the industry and the state, which we argue, should be at the core of any Digital New Deal. In light of the growing data poverty and the lessons learnt from Latin American movements and thinkers, we now examine how the dominant digital paradigm can be reimagined for equity, justice, and sustainable futures. In the following section, we we argue that the Andean indigenous social philosophy of buen vivir – defined as “a way of doing things that is community-centric, ecologically-balanced and culturally-sensitive” – can help us understand the present and collaboratively design a better future for the digital realm and beyond.

Nurturing integrated autonomy: Buen vivir with data

Buen vivir (itself a Spanish translation of the original Quechua sumak kawsay) is translated into English through rather imprecise phrases such as “good living” or “living well”. It points to the harmonious coexistence of human beings with each other as well as the surrounding ecosystem. It is also connected to a sense of the collective. While neoliberalism promotes individual rights, buen vivir shifts priorities away from economic growth as an end in itself towards social and environmental wellbeing and meaningful human connections. It insists that the rights of the individual cannot be disentangled from those of peoples, communities, and nature. Not surprisingly, the notion has gained traction in recent years, finding itself enshrined in Ecuador’s new constitution in 2008 with the recognition of the rights of nature and cultural diversity.

As sustainable development scholar Eduardo Gudynas explains, there are two common misunderstandings that attach themselves to the notion of buen vivir.17 Firstly, buen vivir has often been injected with an idealized return to an imagined idyllic pre-Colombian past. In reality, it is a concept shaped not only by indigenous thinking, but also Western critiques of capitalism over the last three decades, especially in relation to feminist critical thinking and environmentalism. Secondly, while the term has been superficially equated to Western notions of wellbeing and welfare, it is radically different as it focuses not just on the individual and their needs, but is also rooted within the social context of the community and the environmental context in which the individual is embedded. We evoke buen vivir here because it intercepts some of the key concerns illustrated above, most notably the inevitable interconnection between humankind and the environment in the critical ecology approach, the agency of individuals and communities put forward by liberation pedagogy, and the coexistence of ontological difference cherished by autonomous design.

Rather than conceiving buen vivir as a strict blueprint for change, we should view it as a launchpad for fresh thinking and new perspectives.

In the context of the Covid crisis, buen vivir can help us effect an economic and social “reset”18 and rethink our mid- and long-term priorities. Linked to degrowth, the notion can help us redefine how we understand the limits of the dominant digital paradigm. It can inspire us to set new parameters for a future trajectory and prefigure possibilities for contesting the capitalist “there-is-no-alternative” imperative. Through this notion and related rights, we can, for example, reimagine and reorient health, travel, and education away from exploitative models that disregard people, places, and the natural environment and usher in a transformative change in society. At the same time, the focus on buen vivir can promote social and environmental wellbeing and strengthen meaningful human connections.

We should, however, resist the temptation to romanticize the complex notion of buen vivir and strip it from socio-political contexts. Ecuador introduced buen vivir into its constitution not merely as an ethical principle (as in the case of Bolivia) but also embedded it as a set of rights. Yet it failed to manage the current health emergency due to the usual corollary of an overworked hospital system and a helpless population. How, then, should we react to Ecuador’s catastrophic handling of the pandemic? Unfortunately, the analysis of public policies adopted in the last decade reveals a worrying discrepancy between the promises of the official agenda and programs implemented on the ground. There is an evident gap between the principles and rights emanating from the notion of buen vivir and the policies and measures implemented by countries such as Bolivia and Ecuador in response to the crisis. This is why it is imperative to transform buen vivir into a concrete set of policies, activities, and regulations that can improve wellbeing. The ethical principle and the rights that emanate from this concept provide the right direction, but principles and promises must result in on-ground policies and measures that speak to the lived experiences of the people.19 What the case of Ecuador makes evident is that rather than conceiving buen vivir as a strict blueprint for change, we should view it as a launchpad for fresh thinking and new perspectives that “helps us see the limits of current development models and […] allows us to dream of alternatives that until now have been difficult to fulfil.”

If “living with data”20 is our inevitable present and post-pandemic future, can we imagine a buen vivir for the datafied society? We argue that buen vivir with data entails foregrounding at least three key ingredients. The first concerns the fusion of the social with the ecological question, or in other words, the search for a harmonious relation between human and nature. This is obviously of paramount importance in an age of climate emergency. However, it also entails deconstructing the notion that a datafied society is inherently the green alternative to the fossil fuel era. The data economy is expected to consume one-fifth of global electricity by 2025, but this figure corresponds to the pre-pandemic energy consumption. In 2016, data centers had the same carbon footprint as the aviation industry. A Digital New Deal must seek to put the social and the ecological questions at the core as the two are intimately connected.21

A Digital New Deal must seek to put the social and the ecological questions at the core as the two are intimately connected.

The second ingredient for a buen vivir with data points to the necessary dialogic and participatory approach that must be at the center of any decision-making that concerns people, paving the way for the autonomy of and an active role for communities in shaping their datafied futures. Without downplaying the role of expertise in a global crisis like the one we currently face, centering dialogue à la Freire generates situated knowledges and individual as well as collective empowerment.

Finally, the third ingredient in our list has to do with a “localized, relationship-oriented”22 practice of community care and solidarity based on the acknowledgment of ontological difference as well as commonalities. We have seen many instances of this spontaneous solidarity at play during the pandemic, as testified by the blog ‘Covid-19 From the Margins’, among others.23 Rather than just filling in for the (many) failures of the (welfare) state, solidarity and community care should be seen as a way to reclaim agency and sovereignty while defining the kind of societies we want to live in. An ambitious and much-needed green recovery program based on environmentally-friendly growth and an expansion of renewable energy in Latin America can offer a platform where the diverse elements foregrounded in this intervention can be reconciled and experimented with. Only in this way can we hope to reconcile a Digital New Deal with local preferences, values, customs, worldviews, and practice, and make room for a sustainable digital future.

Notes

- 1 Simone Natale and Emiliano Treré, “Vinyl Won’t Save Us: Reframing Disconnection as Engagement,” Media, Culture & Society 42, no. 4 (2020): 626–33, https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443720914027.

- 2 Stefania Milan and Emiliano Treré, “The Rise of the Data Poor: The COVID-19 Pandemic Seen from the Margins,” Social Media + Society, no. July (2020), https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120948233.

- 3 Shoshana Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism (New York: Profile Books, 2019).

- 4 Nick Couldry and Ulises A. Mejias, “Data Colonialism: Rethinking Big Data’s Relation to the Contemporary Subject,” Television & New Media 20, no. 4 (May 1, 2019): 336–49, https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476418796632.

- 5 Milan and Treré, “The Rise of the Data Poor: The COVID-19 Pandemic Seen from the Margins,” 2.

- 6 Joan Martinez-Alier, “Ecology and the Poor: A Neglected Dimension of Latin American History,” Journal of Latin American Studies 23, no. 3 (1991): 621–39.

- 7 Alejandro Carretero Barranquero and Chiara Saez Baeza, “Latin American Critical Epistemologies toward a Biocentric Turn in Communication for Social Change: Communication from a Good Living Perspective,” Latin American Research Review 52, no. 3 (2017): 435, https://doi.org/10.25222/larr.59.

- 8 Martinez-Alier, “Ecology and the Poor: A Neglected Dimension of Latin American History,” 636.

- 9 Moacir Gadotti, Pedagogia Da Terra (São Paulo: Petrópolis, 1990), 15 (authors’ translation from the Portuguese original).

- 10 Martinez-Alier, “Ecology and the Poor: A Neglected Dimension of Latin American History,” 623.

- 11 Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed (New York: Continuum, 1968); see also Ana Cristina Suzina and Thomas Tufte, “Freire’s Vision of Development and Social Change: Past Experiences, Present Challenges and Perspectives for the Future,” International Communication Gazette 82, no. 5 (July 31, 2020): 411–24, https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048520943692.

- 12 R. Stahler-Sholk, “Resisting Neoliberal Homogenisation. The Zapatista Autonomy Movement,” Latin American Perspectives 34, no. 2 (2007): 48–63.

- 13 Arturo Escobar, Designs for the Pluriverse. Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018), xiii, xvi.

- 14 Escobar, xvi–xvii.

- 15 Stefania Milan, “Techno-Solutionism and the Standard Human in the Making of the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Big Data & Society, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951720966781.

- 16 Stefania Milan and Emiliano Treré, “Big Data from the South(s): Beyond Data Universalism,” Television & New Media 20, no. 4 (2019): 319–35, https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476419837739.

- 17 Eduardo Gudynas, “Buen Vivir: Today’s Tomorrow,” Development 54, no. 4 (2011): 441–47, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1057/dev.2011.86.

- 18 Phoebe Everingham and Natasha Chassagne, “Post COVID-19 Ecological and Social Reset: Moving Away from Capitalist Growth Models towards Tourism as Buen Vivir,” Tourism Geographies, 2020, 555–66, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1762119.

- 19 Naomi Joy Godden, “Community Work, Love and the Indigenous Worldview of Buen Vivir in Peru,” International Social Work, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872820930254.

- 20 Deborah Lupton, “How Do Data Come to Matter? Living and Becoming with Personal Data,” Big Data & Society 5, no. 2 (July 1, 2018): 2053951718786314, https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951718786314; Helen Kennedy, “Living with Data: Aligning Data Studies and Data Activism Through a Focus on Everyday Experiences of Datafication,” Krisis: Journal for Contemporary Philosophy 1 (2018), http://krisis.eu/living-with-data/.

- 21 Martinez-Alier, “Ecology and the Poor: A Neglected Dimension of Latin American History.”

- 22 Godden, “Community Work, Love and the Indigenous Worldview of Buen Vivir in Peru.”

- 23 Stefania Milan, Emiliano Treré, and Silvia Masiero, COVID-19 from the Margins: Pandemic Invisibilities, Policies and Resistance in the Datafied Society (Amsterdam: Institute for Networked Cultures, 2020).

Stefania Milan (stefaniamilan.net) is Associate Professor of New Media and Digital Culture at University of Amsterdam. Her work explores the interplay between digital technology, activism and governance. Stefania is the Principal Investigator of DATACTIVE (data-activism.net) and “Citizenship and standard-setting in digital networks”, funded by the European Research Council and the Dutch Research Council. In 2017, she co-founded the Big Data from the South Research Initiative, investigating the impact of datafication and surveillance on communities at the margins. Stefania is the author of Social Movements and Their Technologies: Wiring Social Change (Palgrave Macmillan, 2013/2016) and co-author of Media/Society (Sage, 2011).

Emiliano Treré is Senior Lecturer in Media Ecologies and Social Transformation in the School of Journalism, Media and Culture (JOMEC) at Cardiff University, UK. He’s globally recognized as a ‘bridge’ between the Western and the Latin American traditions at the intersection between communication, activism and data studies. He’s a member of the Data Justice Lab where he’s the Co-PI of the project ‘Towards Democratic Auditing: Civic Participation in the Scoring Society’, funded by the Open Society Foundations. He is also the co-founder of the ‘Big Data from the South’ Research Initiative. His monograph Hybrid Media Activism (Routledge, 2019) won the Outstanding Book Award of the Activism, Communication and Social Justice Interest Group of the International Communication Association.

Together with Silvia Masiero from the University of Oslo, Stefania and Emiliano are the editors of the open access book COVID-19 from the Margins: Pandemic Invisibilities, Policies and Resistance in the Datafied Society (Theory on Demand Series, Institute of Network Cultures, 2021) that stems from a blog with the same title launched in May 2020 and represents a snapshot of the datafied society during the pandemic, amplifying the marginalized voices of 75 authors from 25 countries in 5 languages.