Because my parents treat me like a boy I am allowed to wear shorts, visit places alone and meet my friends.

– Teja (kishori)

In a Foucauldian framework, power resides in social relations and set ups as an everyday socialised and embodied phenomenon. It was these everyday experiences that were used in a series of activities by the Prakriye team to help kishoris access and unpack these power structures and make visible the ways in which they manifested in their lived realities.

The Power Game

In this activity, kishoris were lined up in a single file and assigned the roles of girls and boys or men and women. They were then posed a set of statements that underscored various forms of privilege. For each statement that was true for their assigned role, kishoris could take a step forward. Some statements used were – ‘You are involved in the local legal forum’ or ‘You can sit and chat with friends in any public space in the village’ and ‘You earn more than your family members.’

After all the statements were announced and qualifying steps taken, the ‘men’ in the activity were found to be on the front while the other kishoris were visibly left behind. For the kishoris, this activity demonstrated the intricate details of privilege that go unnoticed.

On being asked what the kishoris felt about the activity, they opened up on their difficulties in navigating the public space and expressing opinions and ideas freely. It was difficult for them to speak up in public discussions and debates because society didn’t value their opinions, and they feared that they would most likely be made fun of. Simple pleasures like going out to watch movies with friends, visit public libraries, or even sit on the aralikatte (a community arena) and chat with one another are impossible for girls, burdened as they are with safeguarding the family’s image in accordance with the norms of the society.

Kishoris were also able to talk about the preference for male children and how when the first child is a girl, parents would keep trying for a boy. When probed on these assumptions, they engaged with the common belief in their communities and villages that salvation comes to only those whose last rites are performed by a son, while those with only daughters will get stuck in the cycle of birth and re-birth. This superstition along with the notion that daughters are a burden and belong to their husbands’ households go a long way in making young women and girls feel unwanted. Challenging these belief systems is a constant and important component of our work with kishoris.

A kishori named Teja opened up about how her parents have always raised her as a boy, since they don’t have one. Like her parents she also feels that only males have the freedom to move around and wear what they like. Teja’s example puts one in a dilemma as to what the true nature of gender equality is. The Prakriye team tried to explain to her that she may not have to behave like a boy in order to be free. Teja responded that it would be disadvantageous for her at this point to take up such a stand as the parents may not understand, the notion that living like a girl would risk her liberty like it does for other girls around, has also deeply settled in her mind.

Where to be and Where not to be

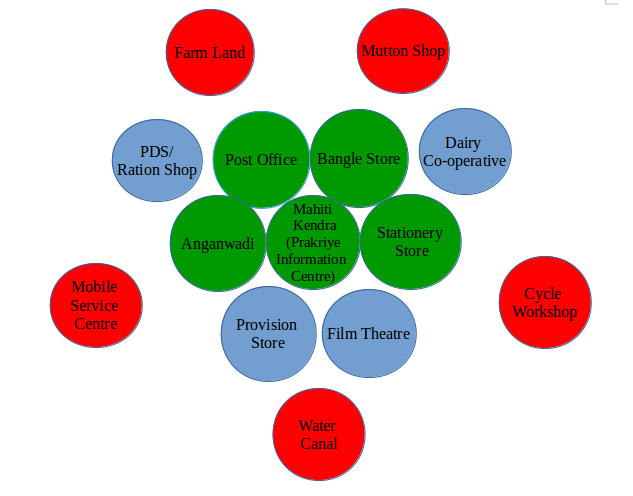

In this activity, the kishoris were asked to list out various spaces in the village and classify them into colours. Green symbolized unrestrained access, blue symbolized access that was possible in the presence of family members, and red meant no access at all as depicted in the illustration below:

Through the activity, it was discussed how parents considered it safer for their daughters to avoid blue and red spaces, because they were largely occupied by males, and they don’t want their daughters to be noticed or harmed. But the kishoris brought up an interesting point – that most women were not restrained from visiting the blue and red areas such as the mutton shop or the water canal in other villages and cities because there is an empowering anonymity when one steps out of the native place, which makes them more confident and enterprising. Kishoris were able to articulate the real problem of being ‘tied’ in a particular space, where they are being constantly monitored by people around them, because the proximity in the village is ever present and most people know each other, in turn affecting their ability to be mobile.