Introduction

Across the globe, a handful of Big Tech corporations have come to occupy central nodes amidst today’s digitalizing and platformizing economies, controlling much of the core infrastructure undergirding its development. Their central quasi-monopoly positions allow these companies to extract growing sums of money, or rents, from their users, suppliers, customers, etc. Their business strategies, based on the effective digital enclosure of social exchange (and their accompanying data flows) in areas such as communication, commerce, and information, have enabled Big Tech corporations to outpace the wider corporate sphere in profitability and market capitalization. In a self-reinforcing feedback loop, this financial firepower then allows them to anchor and augment their infrastructural dominance in the digital universe. As a result, the space for new entrants becomes increasingly curtailed in the digitalized platform economy while our social and societal dependence on Big Tech incessantly deepens, as has been evident during the pandemic.

That said, a brewing unease has prompted governments and civil society to question the centralization of digital power, a process we describe as “Big Techification”, whereby, a few Big Tech companies increasingly shape and control the wider development of “platform capitalism”. For one, the unrestricted way in which data is gathered, analyzed, and put to work to erect a regime of “surveillance capitalism” has stimulated debate over how to govern social exchange and information and foster alternatives — a development boosted further by pandemic politics. Besides, the various political and economic aspects of Big Tech’s individual and combined monopoly power have breathed new life into old debates, ranging from economic development to the foundations of democracy.

The View from Europe

The view from the European Union (EU) is particularly interesting in this regard. Having no homegrown Big Tech companies of its own and relying extensively on the five American Big Techs (Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta, and Microsoft, which are collectively referred to as the Big Five), the EU remains a major player shaping global market regulations. Its legislative power often functions as a stepping stone towards global standards, which some refer to as “the Brussels effect”. The term refers to the regulatory power of the EU, which influences companies globally and pressurizes them to adopt EU compliance standards. By implementing EU standards to their global operations, these companies reduce costs and the complication of complying with multiple regulatory regimes. The adoption of the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) by large companies across the globe is a prominent example of the Brussels effect in digital markets. Therefore, through the normative power of the Brussels effect, the EU might be well-equipped to tame the relentless onslaught of Big Techification.

EU’s legislative power often functions as a stepping stone towards global standards, which some refer to as “the Brussels effect”. The term refers to the regulatory power of the EU, which influences companies globally and pressurizes them to adopt EU compliance standards. By implementing EU standards to their global operations, these companies reduce costs and the complication of complying with multiple regulatory regimes.

In this essay, we first outline the general contours of Big Techification, highlighting the interplay between the operational and financial workings of the largest tech incumbents. The second part zooms in on the EU’s latest legal proposal, known as the Digital Markets Act (DMA), to arrive at ways to regulate the “data-driven intellectual monopolies” of Big Tech. Our analysis demonstrates that the EU is at the heart of the extraterritorial reach of American Big Tech firms, but is also actively involved in promulgating a regulative regime to accommodate, steer, and ultimately tame Big Techification i.e., the corporate enclosure of the “infrastructural core” of platform capitalism driven by the Big Five. Crucially, however, at the time of writing this essay, the global reach or Brussels effect of the recent DMA remains limited, and it remains to be seen to what extent this body of law could be replicated outside the EU, not least across the Global South. As such, the case of the DMA serves as a learning ground for activists and policymakers concerned about the all-pervasive nature of Big Techification.

1. Big Techification: A Brief History

The history of Big Tech starts with the development of a post-war military-industrial complex in the United States, with Stanford University leading the development of a range of innovations that would eventually shape the rise of information and communication technologies (ICT). Although sparked by massive public investments, emergent ICT infrastructures like the internet were opened up to private corporations in the course of the neoliberal 1990s. These political decisions of privatizing publicly-funded innovations, coupled with a growing nexus between Wall Street and Silicon Valley, including the venture capital (VC) model that ensured access to capital, laid the groundwork for the present-day “privately-owned public spaces”.

1.1 Big Tech Bang

The 1970s were characterized by hardware developments, with IBM featuring as the dominant firm, and the 1971 invention of Intel’s microprocessor foreshadowing the advent of personal computers (PCs). Between the 1980s and the early 1990s, the orientation in ICT development shifted to software interoperability as the diminishing clout of IBM gave way to the rise of Microsoft. Building on these ICT developments, the commercial rollout of the internet in the 1990s heralded the age of digital platforms. The emergence of the likes of Amazon, Google (the parent entity that is now Alphabet), and Facebook (now Meta) between 1994 and 2004 constituted a “Big Tech Bang”, while the older Big Tech companies, i.e. Apple and Microsoft, established in the 1970s, steadily expanded their platform operations.

With the birth and consolidation of the Big Five completed around the turn of the millennium, developments like the dot-com crash and 9/11 ignited the age of deployment, steadily expanding the Big Five’s data-hungry reach throughout economies and societies. The 2007 invention of Apple’s iPhone massively expanded the scale and scope for data extraction, as PCs effectively morphed into mobile smartphones, boosting global connectivity and enabling the abundant development of personalized applications, with mounting volumes of data stored in expanding cloud infrastructures. As the Big Five increasingly turned into the infrastructural core they are today, myriad digital platforms such as Airbnb, Netflix, Spotify, and Uber developed upon and around it. As Van Dijck et al. argue, smaller, nationally variegated and/or sectoral platforms that have emerged under the wider process of platformization typically rely and are built upon the Big Five’s core infrastructural platforms, from the hyper-scale clouds at the back end to the operating systems and app stores at the front end, boosting the process of Big Techification. Likewise, existing industries have rapidly embraced the promises of platformization, including the world of ‘haute finance’. By relying on the Big Five toolbox, these industries boost Big Techification. Since the 2010s, the global reach of the American Big Techs has been increasingly challenged by Chinese competition, spearheaded by the likes of Alibaba and Tencent, which collectively constitute a Chinese Big Tech ecosystem that combines mounting technological acumen with rapid societal deployment under authoritarian state control.

Put together, these developments have propelled the digital power of Big Tech and set the stage for “the Big Techification of everything”. In the present day, the consolidation of Big Techification is shaped by rapid advances in the fields of artificial intelligence (AI), fifth-generation mobile communication (5G), and the so-called Internet of Things (IoT), connecting more and more applications and devices to the infrastructural core of the digital economy. Despite mounting efforts, most states have thus far exhibited serious deficiencies in their capacity to rein in the advance of Big Tech. States are especially hindered by the fact that the Big Five monetize their operations in ways that are not compatible with established principles and legislation to regulate capitalism. For example, Big Tech is at odds with the existing cross-border allocation of tax rights, resulting in large-scale tax avoidance and non-taxation. The speed at which these companies have developed — some have recently been valued at more than USD 2 trillion on the stock market,— is in sharp contrast with the much slower pace at which civil society and governments have been able to grasp, let alone regulate, the transformative nature of these firms.

In the present day, the consolidation of Big Techification is shaped by rapid advances in the fields of artificial intelligence (AI), fifth generation mobile communication (5G), and the so-called Internet of Things (IoT), connecting more and more applications and devices to the infrastructural core of the digital economy. Despite mounting efforts, most states have thus far exhibited serious deficiencies in their capacity to rein in the advance of Big Tech.

1.2 Big Tech Model

Although the Big Five have each cornered different digital markets, such as retail (Amazon), professional life (Microsoft), and advertising (Alphabet), their operations often overlap, as is the case for these three Big Techs which jointly dominate cloud services. In fact, despite their differences, we argue that it is possible to speak of a generic “Big Tech model” through which these companies augment their digital sway. This model essentially combines first-mover advantages and network effects to help the companies corner particular digital activities, and generate and augment digital market dominance. The key infrastructure delivering these services is ‘the platform’, which enables and regulates the interaction of multiple user groups. This infrastructure effectively rearranges the decentralized web into a limited number of centralized corporate nodes, which increasingly function as ‘obligatory passage points’ for communication, search, consumption, and so forth. In so doing, the Big Five escape market pressures, and instead become the gatekeepers of the core infrastructures undergirding platform capitalism. As Peck and Phillips argue, “The real home of platform capitalism is the zone of the antimarket, a murky but dominating layer above the competition, where it operates as a new machine with an old purpose.”

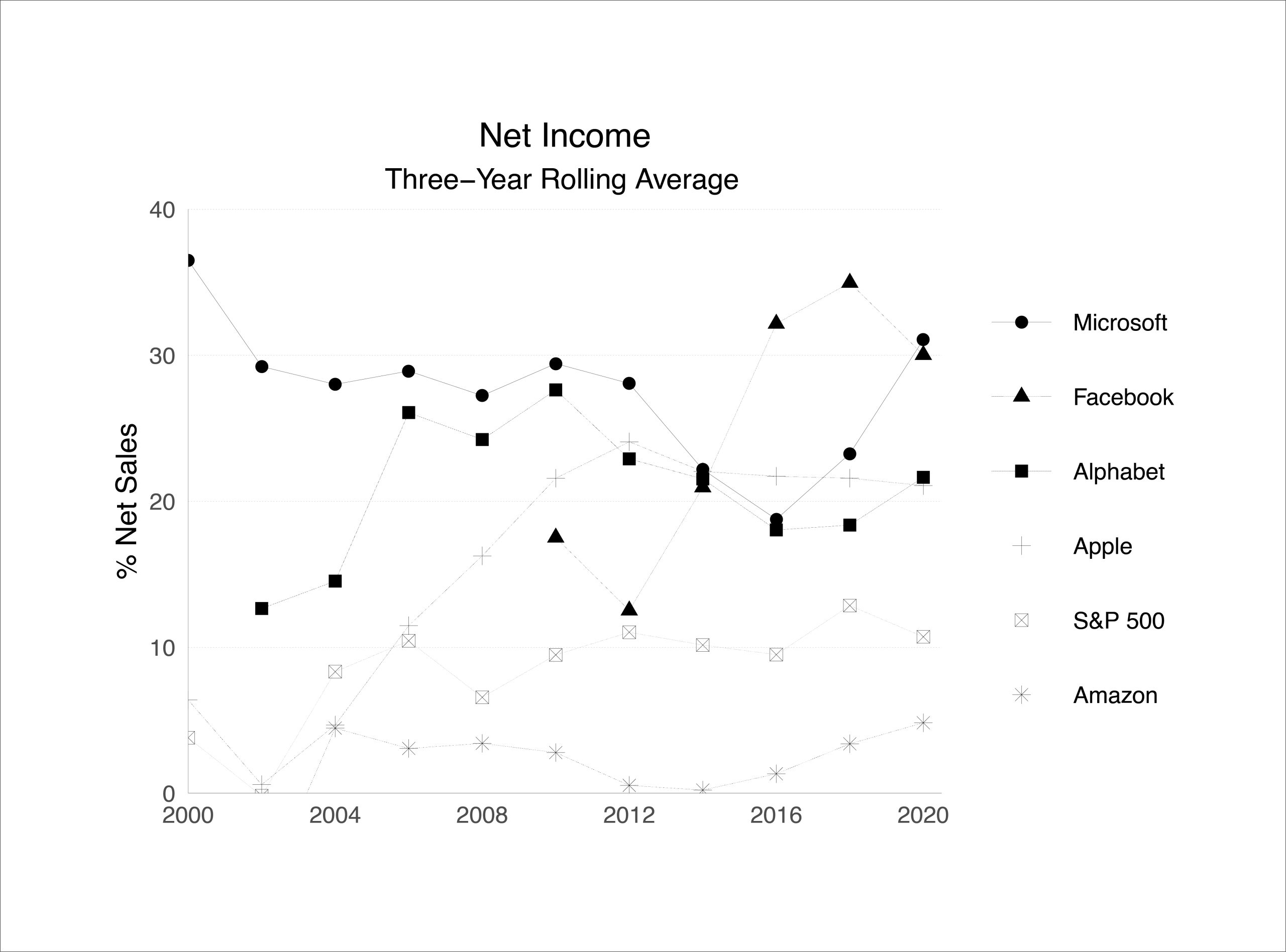

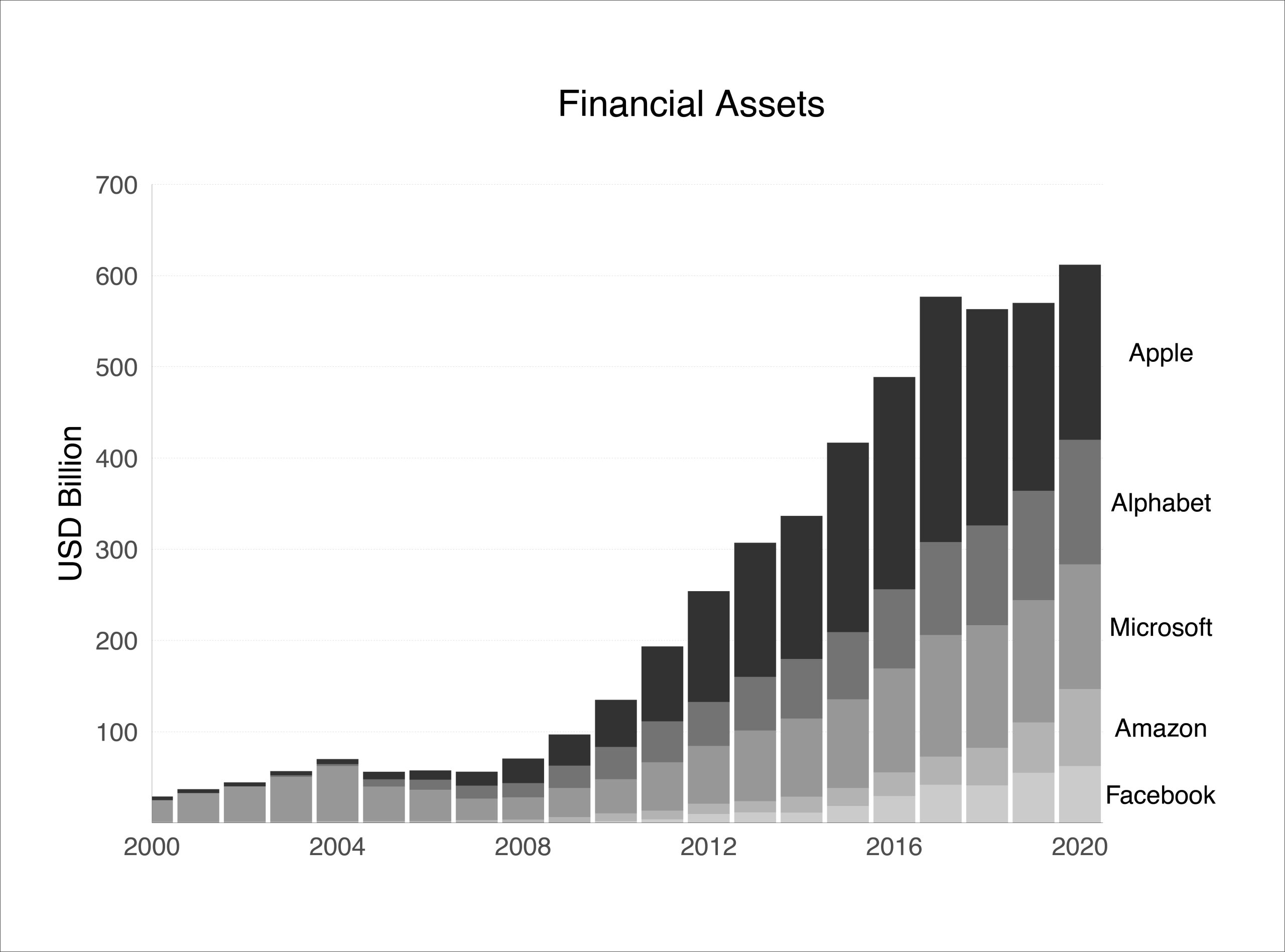

The Big Five’s quasi-monopoly positions result in above-average profitability, which they use to further augment their infrastructural power over platform capitalism in both scale and scope, either by reinvesting or through acquiring other firms. It is well-known by now that the profits of the Big Five (Figure 1) far exceed those of other firms, allowing them to accumulate large volumes of financial assets. In 2020, their combined financial assets rose to USD 612 billion from USD 135 billion a decade ago (Figure 2). In 2020, Apple alone held cash, short-term investments, and securities worth an unprecedented USD 192 billion, notably after selling off securities in the years before. The financial assets of Alphabet and Microsoft stood at USD 137 billion each in the same year.

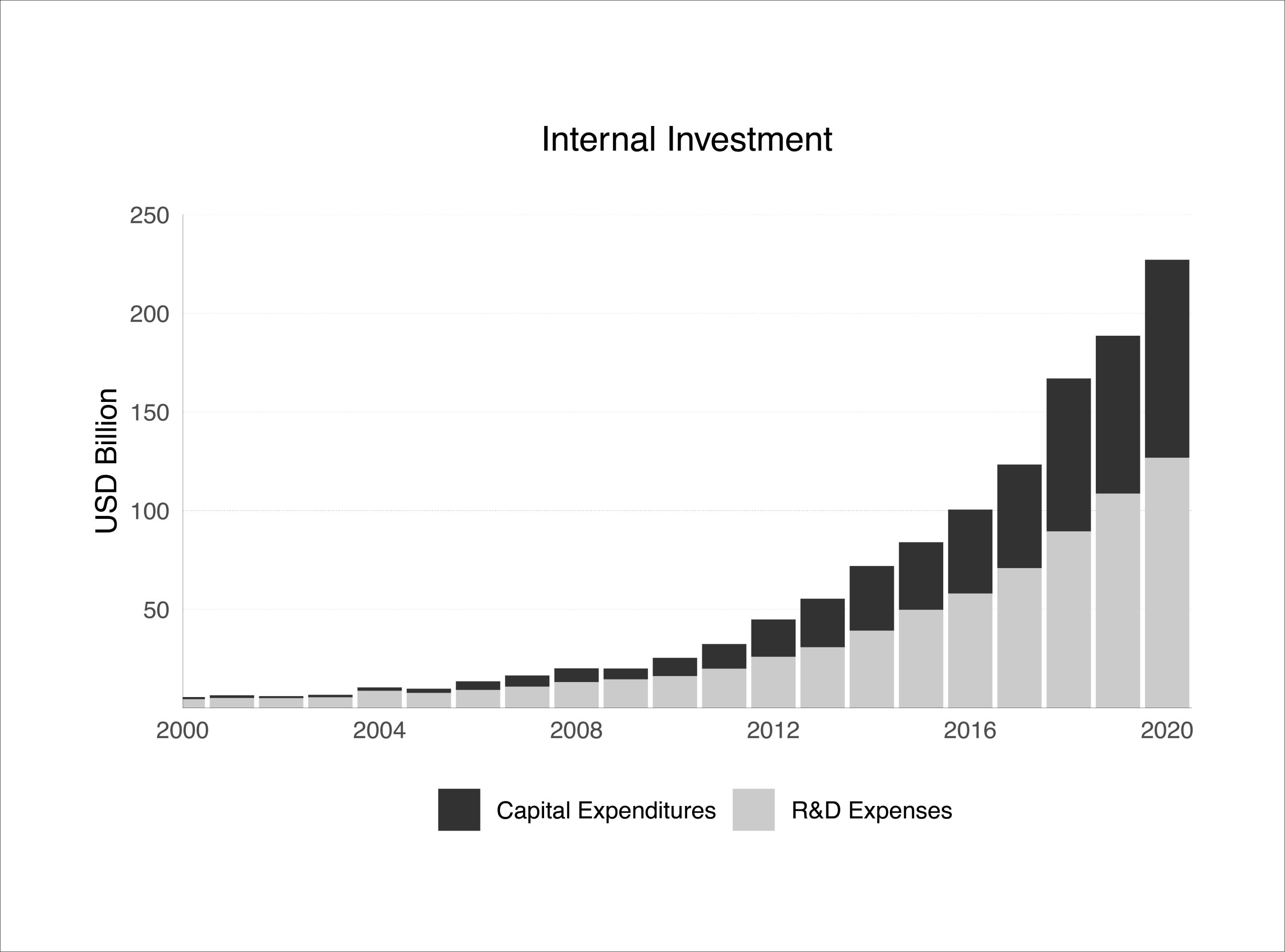

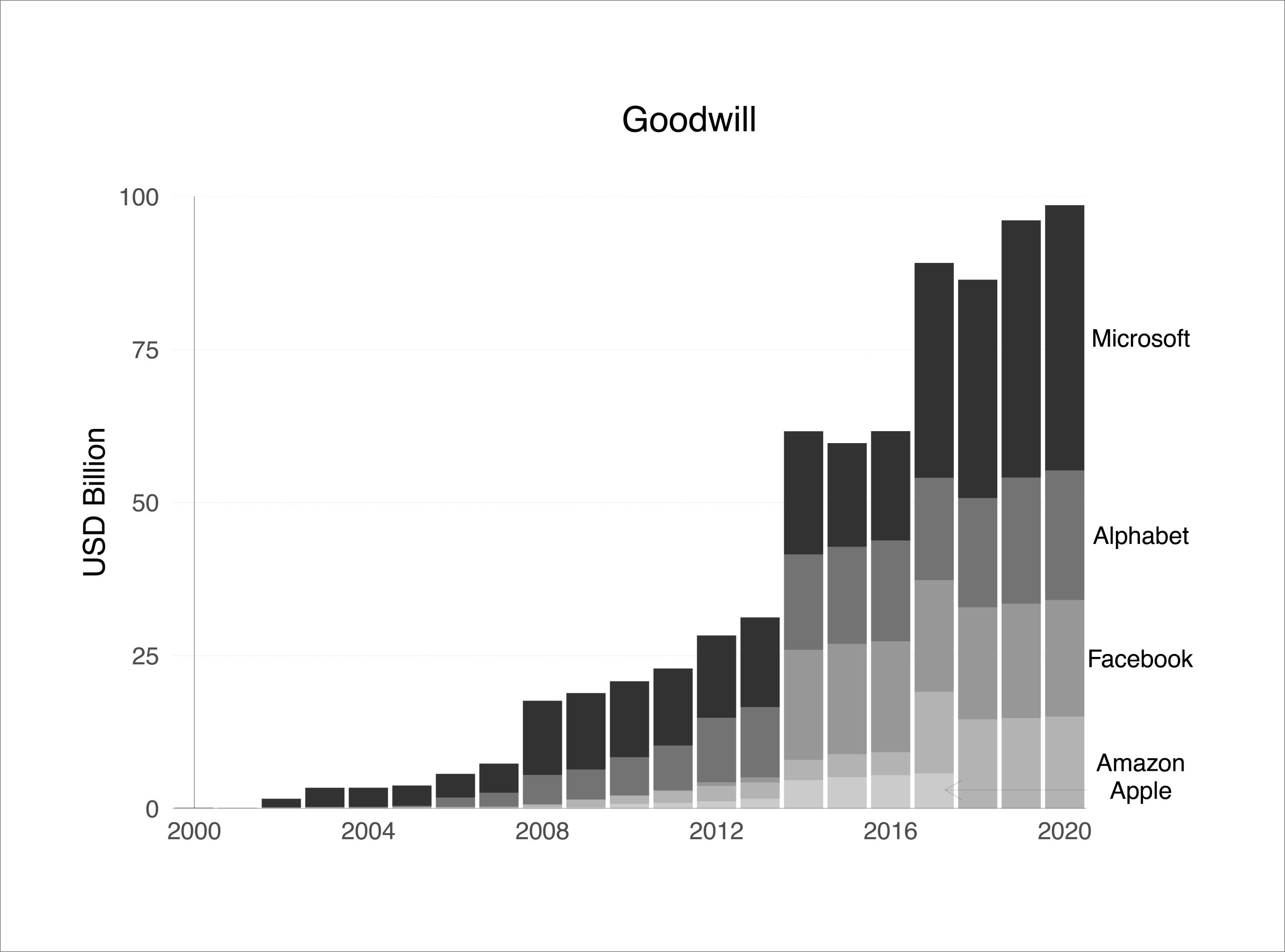

Figure 1-4 SEQ Figure: Profitability, Financial Assets, Internal Investments, and Goodwill of the Big Five

(Own calculations on the basis of Refinitiv Eikon Worldscope and annual reports. Note that Apple ceased to report intangible assets/goodwill in 2017.)

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Strong cash flows allowed the Big Five to reinvest heavily in tangible and intangible capital through capital expenditures and research and development (R&D) expenses, respectively. Between 2010 and 2020, their combined internal investments grew eight times, from USD 25 billion to USD 227 billion. Amazon alone spent USD 83 billion in 2020, far ahead of its peers Alphabet (USD 50 billion) and Microsoft (USD 35 billion) (Figure 3). This organic growth was further enhanced by expansive acquisitions, the majority of which targeted other US-based firms. The numbers in Table 1 likely understate the importance of acquisitions as they only include full acquisitions. We can, however, assess how critical acquisitions are for Big Tech by tracking the quantum of ‘goodwill’ assets — defined as the premium paid by the acquiring firm over the value of the acquiree’s net identifiable assets (that is, assets less liabilities) — on their balance sheet. The results confirm that acquisitions have become an important component of the Big Five’s growth strategy, most strikingly illustrated by goodwill assets worth USD 43 billion on Microsoft’s books in 2020 (Figure 4). In January 2022, the company made headlines when it announced the acquisition of gaming developer Activision Blizzard in an ‘all-cash’ transaction valued at USD 69 billion, prompting scrutiny among regulators on both sides of the Atlantic. Buying other tech firms, thus, sits at the heart of the Big Five’s ability to expand their respective infrastructural might. But this ability is difficult, if not impossible, for potential competitors to match.

Table 1: Big Five Acquisitions

| Name | Year founded | IPO | Year of first acquisition |

Proportion of U.S.-based acquisitions |

Number of worldwide acquisitions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microsoft | 1975 | 1986 | 1987 | 235 | 69% |

| Apple | 1976 | 1980 | 1988 | 109 | 61% |

| Amazon | 1994 | 1997 | 1998 | 94 | 70% |

| Meta | 2004 | 2012 | 2007 | 81 | 68% |

| Alphabet | 1998 | 2004 | 2001 | 237 | 74% |

Source: Compiled from data in Feldman et al. 2021.

The multi-sided markets of platforms have long been deemed subject to a ‘winner-takes-all’ logic. The threat posed by this logic to market competition has prompted the European Commission (EC), among others, to table new legislation. Other attempts to tame Big Techification through regulation have been unfolding from the United States to China, in various guises seeing the state (threatening to) step in to tame their homegrown Big Techs, seeing Ant Financial and its owner Jack Ma (Alibaba) being reined in by the Chinese Communist Party. The European effort will take longer to materialize and will be subjected to modifications, made by corporate interests at the national and European level, which is characteristic of how ‘the Brussels bubble’ operates. Moreover, regulating Big Tech is not simply a matter of individual (national) jurisdictions facing transnational (global) corporate structures, but includes myriad geopolitical, economic, and strategic dimensions that will define the contours of the 21st century global political economy.

2. The Regulatory Response from the EU: The Digital Markets Act

The DMA is a 2020 legislation proposed by the EC to ease the entry of new participants into digital markets, and prevent the abuse of dominant positions by market incumbents led by the Big Five. The DMA builds on the EU’s GDPR. But unlike the GDPR, which is solely concerned with the protection of data privacy, the DMA focuses on regulating digital monopolies. Also, unlike the GDPR, the DMA does not apply to all platform services in the EU, but is limited to core platform services of so-called gatekeepers, chiefly the Big Five, with the aim to protect digital markets and create space for non-gatekeepers.

The DMA creates a class of data custodians, described as gatekeepers, which are defined by their market position and market capitalization, and subject to obligations and prohibitions that are in part intended to limit rent-seeking. The application of the DMA’s obligations and prohibitions has the underlying intention of expanding the market for smaller (domestic) participants, and thus limiting corporate enclosure by foreign Big Techs. The aim is to limit the gatekeepers’ ability to foreclose access to digital markets, in order to encourage the distribution of digital rents to smaller market participants. For the most part, however, the DMA’s controls on gatekeeper rent-seeking seem rather limited.

Gatekeepers are categorized based on two factors. The first factor is the extent of provision of “core platform services” which determines the dominant positions of each of the Big Five (Table 2). Core platform services refer to commonly used digital services such as search engines, marketplaces and app stores, cloud services, etc., and the extent of provision of these services determines the multi-faceted nature of the platform. The second factor is the market share of the company, indicative of market dominance and rent-seeking abilities.

Table 2. Definition of a ‘Gatekeeper’ according to the DMA

| Core Platform Service | Qualitative Criteria | Quantitative Criteria |

|---|---|---|

Exhaustive list includes:

|

|

|

Source: Compiled from DMA Act, 2020.

An important highlight of the DMA is that it has quite serious enforcement mechanisms, with breaches of directly effective and further specified obligations1DMA Articles 5 & 6. attracting fines up to 10% of a gatekeeper’s total turnover in the previous financial year. Failure to notify regulators about market concentrations, or provide audited descriptions of techniques for the profiling of consumers,2 DMA Articles 5 & 6. attract fines not exceeding 1% of total turnover in the previous year, followed by incrementally increasing fines for continuing non-compliance. Article 16 allows for specific performance and further divestiture remedies for extreme cases. In keeping with the ‘ex-ante’ theme of the DMA, the Commission has the power to amend the regulation’s content, if need be.

As such, the DMA would not address market abuses perpetrated by non-gatekeeper undertakings. Similarly, DMA prohibitions and obligations only apply to core platform service-based abuses, and do not necessarily extend to “innovations” in gatekeeper rent-seeking. Innovations here can be defined as new areas, forums, or modes of rent-extraction that are contingent on manipulating and developing access to platform features.

In spite of any definitional flexibility in the DMA and the possibility that the Commission may designate digital market participants as gatekeepers in conjunction with the ‘ex-ante’ model of the DMA, its scope for countering Big Techification is not all encompassing. In all likelihood, the DMA seeks to avoid pre-emptive prohibitions of hypotheticals. By not legislatively precluding developments in digital technology, it can rely on the emergence of post-DMA case law to identify offensive innovations, in congruence with the general body of European Competition law.

An important limitation of the DMA is that it proposes very little in terms of merger control relating to ‘killer acquisitions’ by the Big Five. A killer acquisition can be defined as the acquisition of innovative target undertakings, with a view to discontinue or appropriate such innovations and pre-empt future competition.

Another important limitation of the DMA is that it proposes very little in terms of merger control relating to ‘killer acquisitions’ by the Big Five. A killer acquisition can be defined as the acquisition of innovative target undertakings, with a view to discontinue or appropriate such innovations and pre-empt future competition. Instead, the DMA merely provides for an obligation on gatekeepers to inform regulators about market concentrations under Article 12. This suggests that the current EU merger-control regime shall suffice. This is problematic, particularly as most previous Big Five acquisitions were not subject to competition authority scrutiny, as these did not meet turnover thresholds and those reviewed3Article 22 of the European Union’s Merger Regulation (EC/139/2004) allows Member States to request the Commission to examine concentrations in excess of EU turnover merger control thresholds. were not blocked under current merger control procedures.4 Although the intended acquisitions to be informed about are proposed to be defined with reference to the EU Merger Regulation (EC/139/2004). The DMA Article 12 obligation marginally improves on the current EU merger control regime. New EC merger-control guidance does, however, refer to merger referral-targeting of transactions (Article 22 EU Merger Regulations) in the digital and pharmaceutical sectors. This includes start-ups or recent entrants with significant competitive potential, important innovators, or providers of products or services that are key inputs for other industries, where the value of consideration received by the seller is higher in comparison to the current turnover of the target. This guidance nevertheless remains reliant on ‘ex-post’ referral to the Commission and is legally and formally unrelated to the DMA.

Compared with the DMA’s non-enforceability of obligations, data portability, and blacklisted action, it advantages non-gatekeeper, EU platform capital over gatekeepers by offering the former a captive source of end-user rents, with the Commission carving out an exclusive regulatory jurisdiction over the Big Five and other foreign (primarily U.S.) platforms operating in the EU that compete with and provide services to EU business users. Put differently, it might be argued that the DMA aims to advance competitive EU platformization by taming US Big Techification. The DMA has an almost ordoliberal purpose — ordoliberalism is the German variant of neoliberalism which sees the role of the state as integral to ensuring the smooth operation of markets — in that it seeks to protect the competitive ability of companies as opposed to competition as a whole. In competition policies, private interests can only remain in check through the intervention of strong governments. The DMA’s ordoliberal underpinnings are manifest in its disproportionate focus on the largest platform-capital market participants, a focus which does not seem to be directly congruent with existing EU competition law. There is little consideration given to smaller (and indeed EU) platformed undertakings, potentially engaged in similar market abuses, simply for there being very few EU companies that meet the DMA gatekeeper threshold requirement. As said, the EU has no home-grown Big Techs.

In this context, the DMA, alongside EU Competition policy in general, is accused of being protectionist and “driven by an activist agenda”.5Such as from the Swiss competition commissioner Henrique Schneider in European Union Antitrust Policy in the Digital Era. It has also been suggested that the DMA is geared towards excluding European intellectual monopolies from DMA gatekeeper status, emulating China’s exclusion of U.S. platform capital from its mainland, with a view to nurture its own tech giants.

Unlike most ordinary EU competition law, in being likely to centralize its enforcement at a Commission level, the DMA will not particularly augment or extend any aspect of any consumer welfare outcomes of European Competition law.6 Treaties and regulations are vertically and horizontally (directly) effective as good law in member-states against the state or another individual. Further evidence of such centralization is that although the DMA is proposed to be directly applicable,7 Proposal for a Regulation on Digital Markets Act. 15 December 2020. European Commission. COM/2020/842.

it does not seem to attempt to promulgate regulatory standards to be enacted by member states, at any standard higher than the DMA itself, as seen in other European competition regulation. 8 As under Reg. EC/ 1/2003, although the German Federal Cartel Office (Bundeskartellamt) has pre-emptively introduced comparable (if not superior) regulations under the Act against Restraints of Competition, with similar developments in other EU member statesConsumer welfare is barely touched upon in the DMA, with only a vague reference to end users being “afforded appropriate regulatory safeguards”,9 DMA Para.7 with no indication as to the mechanism by which such protections are to be implemented. The language of the DMA suggests that it is ultimately geared towards protecting business users from the excesses of Big Tech gatekeepers through whom they conduct their businesses, with consumers or end users largely only passively subject to both such business users and gatekeepers. While the DMA offers some important lessons in countering the power of Big Techification, its limitations as a developmentalist, ordoliberal tool lie in the focus on enhancing Europe’s digital or technological sovereignty, overwhelmingly targeting American gatekeepers.

The current global efforts to address Big Tech are weak and exhibit serious deficiencies. The regulations keep following the pre-existing route laid out by competition law and regulations on data privacy. However, the sheer scale of Big Tech and the dynamics of Big Techification cannot be effectively reined in by using the existing toolbox.

The DMA’s regulatory limitations on innovations, including elaborate strategies of regulatory arbitrage, which are constantly being engineered by Big Tech, remain to be seen. Similarly, the impact on mergers also remains a concern. Finally, a regulatory approach which emphasizes transatlantic levelling and geopolitical competition as opposed to a strict consumer protection angle raises the possibility of a reverberating effect across the globe. While countries may adopt aspects of the DMA, it is also important to note that EU’s trade negotiations with countries in the Global South have been shown to hinder the development of domestic platforms and state control over Big Tech. As such, perhaps the DMA will only give impetus to other countries to tame foreign Big Techs, whether American or Chinese, in order to develop and protect their own digital markets and platform companies. As our analysis shows, it won’t be easy.

Conclusion

Over the coming decades, humanity faces a number of historical challenges set in the context of what might be called a finance-led platform capitalism. The first is saving the planet from climate change by drastically reducing the carbon footprint of our societies. This mission is moving much too slowly as corporate interests have downplayed the threat for decades, blocked public intervention outright, and lobbied for states to de-risk financial instruments, ostensibly to move capital in the right direction.

But while addressing climate change has resulted in some form (or façade) of global decision-making, despite all its deficiencies and asymmetric power relations, another big challenge — taming Big Techification — is at a nascent stage mired in geopolitical rivalries. The speed with which Big Tech companies augment their infrastructural dominance, boosted by enormous financial firepower and propelled by a self-reinforcing feedback loop, cannot be matched by existing state bureaucracies. Mainstream economics, meanwhile, remains woefully blind to corporate power and the broader dynamics and effects of data-driven intellectual monopolies. Both these facts are evident in the current regulatory attempt by the EC in the form of the DMA. Overall, whilst the DMA provides some useful small steps forward, particularly for businesses that depend on the Big Tech gatekeepers, the legislation seems too limited in scope to challenge Big Techification.

To tame Big Techification, we need to understand where we are. Besides Big Tech’s mounting infrastructural power over digitizing economies and societies, we stress the importance of the unrivalled financial resources that enable these firms to operate uninhibited in the age of financialized platform capitalism. Together, they buttress the growing dominance of Big Tech, and increasingly test the ability of democracies to set rules and maintain a degree of popular sovereignty vis-a-vis corporate interests.

The current global efforts to address Big Tech are weak and exhibit serious deficiencies. The regulations keep following the pre-existing route laid out by competition law and regulations on data privacy. However, the sheer scale of Big Tech and the dynamics of Big Techification cannot be effectively reined in by using the existing toolbox.

In many ways regulators acknowledge this: they can see that their toolboxes are outdated and insufficient, but states make laws based on long-standing, traditional, and siloed policymaking mechanisms. The epistemic underpinnings of existing forms of statecraft can identify and deal with individual and specific problems pertaining to platform capitalism – it will however take quite some time for states to tame its gatekeepers and the relentless logics of Big Techification.