Your Essay Title Goes Here

by Francois Soulard

DND abstract goes here DND abstract goes here DND abstract goes here DND abstract goes here DND abstract goes here DND abstract goes hereDND abstract goes hereDND abstract goes hereDND abstract goes hereDND abstract goes hereDND abstract goes

Section Title Box

Heading 2

This is what an inline quote looks like. This is what an inline quote looks like. This is what an inline quote looks like. This is what an inline quote looks like. This is what an inline quote looks like. This is what an inline quote looks like. This is what an inline quote looks like. This is what an inline quote looks like. This is what an inline quote looks like. This is what an inline quote looks like.

DND abstract goes here DND abstract goes here DND abstract goes here DND abstract goes here DND abstract goes here DND abstract goes hereDND abstract goes hereDND abstract goes hereDND abstract goes hereDND abstract goes hereDND abstract goes

Heading 2

DND pull quotes go here

The Covid-19 pandemic has put health, political, and economic systems under considerable strain, accelerating a phenomenon already at work in the digital continent and, more broadly, on the security front.

This has exposed a deeply fragmented multilateral stage, torn between geopolitical rivalries and nationalist reflexes while allowing for medium-intensity scientific cooperation. On the one hand, as with the previous health crises of the 2000s such as Ebola, MERS, and SARS, the coronavirus pandemic has created – on a whole new scale – a sense of urgency that has forced the adaptation and invention of innovative responses. On the other, it has provided alibis for certain actors to impose their will, strengthen their control, and manipulate opinions if needed to conquer economic markets, all in the name of efficiency to meet the demands of the healthcare spiral.

The cascading effects of the Covid crisis are not entirely new. Despite the many imperfections in the multilateral framework, the World Health Organization (WHO) has provided the basis for countries to develop crisis responses, with some adaptations to suit their local contexts. And yet, the current crisis remains marked by extreme operational vulnerability, irrespective of the degree of material development in societies.

While the initial sources of the pandemic may have been easily identified and secured, the absence of a steering function for risk modeling, effective response mechanisms, and a coordinated global action required in the face of a threat of this magnitude has landed us in the current debacle. In short, our international system stands bare and archaic, with the G20, the WHO, and other players unable to orchestrate any transnational efforts. As the current crisis has unfolded, it has exposed the flaws in our socio-economic systems and modes of action adopted to cope with the situation.

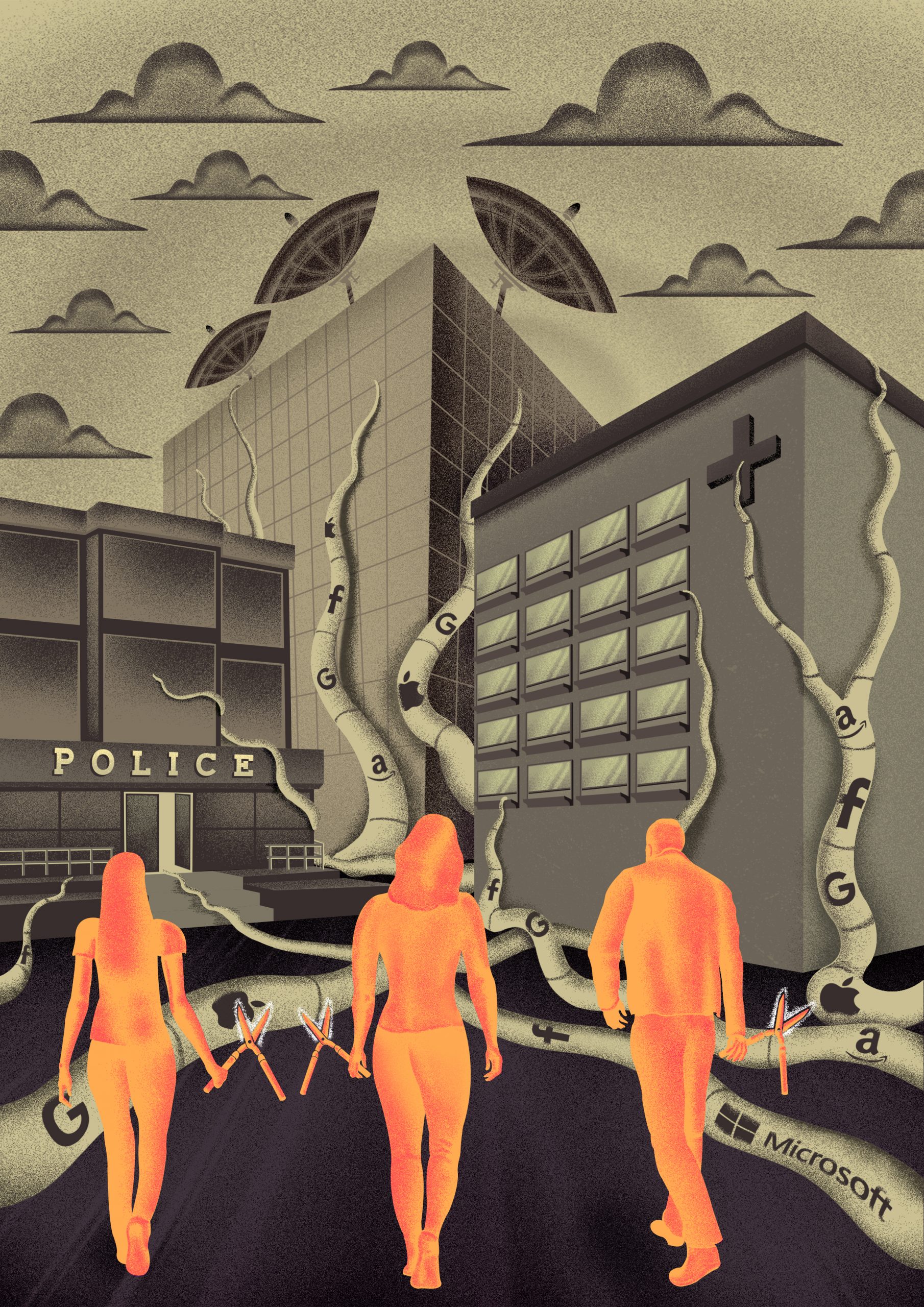

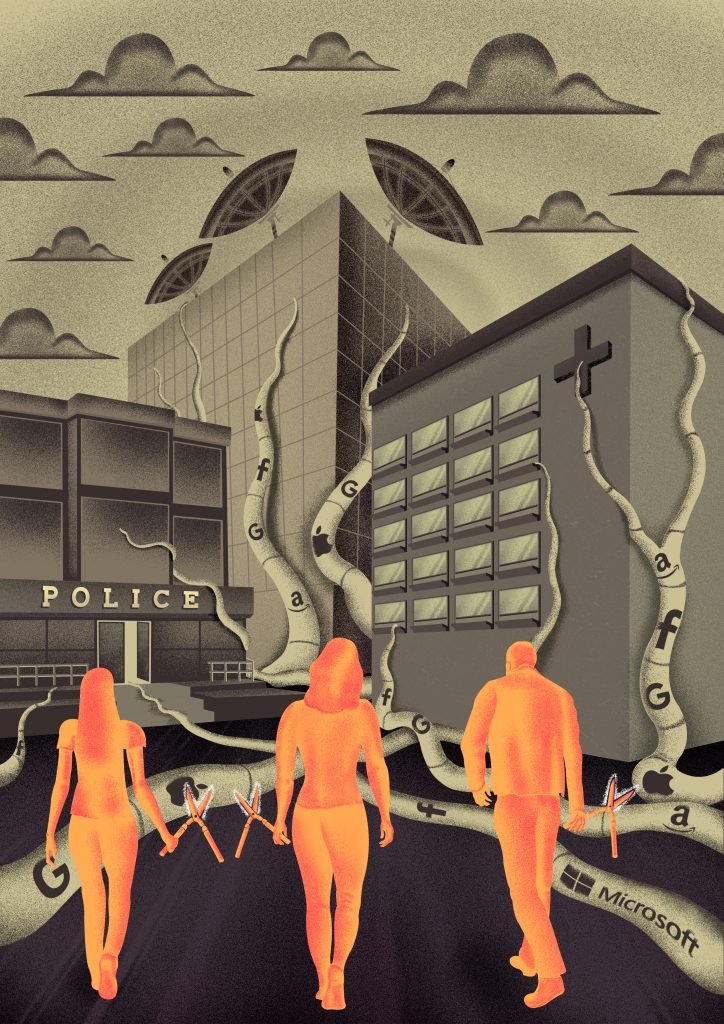

The absence of a globally coordinated response to the pandemic is a missed opportunity to move towards better models than the ones we are currently stranded with. Our current models, relying on a rigid vertical segmentation of productive activities, resulting in the concentration1 and optimization of economic costs in long delocalized chains, have proved to be less resilient to the crisis. Some cards have also been reshuffled in the realm of perceptions, geopolitical relations, technologies, and economics. One of the consequences of the pandemic has been a crude sketching of the world canvas in which we will operate in the decades to come, in which the traditional balance of power, the lack of cooperation, and the assertion of national interests will be the linchpins. New stress points arising from the pandemic and the acceleration of previous trends are likely to seal medium-term arrangements. The crisis has favored a wave of sovereign posturings and affirmations which were already underway at the global level. Big Tech corporations are taking the place of fossil-fuel producers in the stock market podium while clean power shares are up by 45 percent so far in 2020.2

However, unlike the global financial collapse of 2008, the pandemic is an external accident which originated outside the current economic and political matrix. This diagnosis is often challenged on the grounds that the circulation of the virus could have been facilitated by the no-holds-barred extraction of natural resources, unregulated globalization, experimental manipulation of living beings, or even by the authoritarian nature of the Chinese state. Besides, the emergence of every new climate or security risk3 increasingly forces us to re-evaluate existing notions of economic efficiency and pay attention to the long-term variables of resilience and adaptation.

Be that as it may, beyond the ideological sensitivities and despite the intensity of the global economic slowdown, we can see that current responses to the pandemic are not built on the identification of an endogenous fracture in global capitalism. For states and other actors engaged in international exchanges, there has been no real questioning of the engines of the economic status quo. Rather, attention has been focused on the imperative to manage the health contingency and promote recovery, possibly accompanied by certain corrective measures. The focus has also been on a certain strategic reorientation, in particular on the decoupling and relocation of sectors. The recovery plans have been criticized for reinforcing earlier standards of productivism and not taking into account, for example, the new climate commitments4 resulting from the Paris Agreement of 2016.

This initial diagnosis of the origins of the crisis is central because it has determined the forms taken by recovery strategies and their interactions with the digital sphere. We are at a stage where many – including sections of the global economic elite5 – are rushing to underline the contradictions exposed by the pandemic. And yet, there are few signs that it has led to a fundamental shift in the nature of recovery models.6 There is an intensified use of digital technologies to support post-pandemic recovery without any particular awareness of an endogenous crisis in the digital sphere. There are neither new insights in the governance of the digital nor a reorientation in decision-making, only an acceleration of previous tendencies. The computerization of the real economy is one of them.

In this respect, the digital continent, the primary focus of this essay, is perhaps one of the most fertile areas to explore in the present landscape. The shockwaves of the pandemic have brought to the forefront the ethos and physiognomy of “digitization”. This physiognomy needs to be approached carefully through a lens and a vocabulary that can accurately describe the processes at work. Instead of “digitization”, for instance, which only refers to the sub-process of data encoding in a binary format, I will evoke the process of “computerization”. The latter raises the idea of a transformation of the old technical system, constituted by the alloy between the human workforce and machines, into a new one based on the alloy between programmable automatons and the human brain. In this context, the question of cognitive registers is of primary importance. A new understanding is needed to grasp these manifestations in depth and see beyond the parameters defined by the spirit of the times. The difficulty in envisioning computerization as a phenomenon that goes beyond a mere technical disruption is a crucial part of the agenda. This is at the root of the current digital imbalance that exacerbates the impacts in terms of predation and threats, and reduces the potential for a social justice-oriented digital economy. Through negative and positive shocks, the pandemic is offering us a sort of radiography of the characteristics of the new digital economy. This new economy is not merely a new industrial sector, it is “upgrading” the current industrial economy and shaping a new matrix.

this is where the author bio goes

this is where the author bio goes