Author: J Devika

This blog is part of the series ‘Righting Gender Wrongs’ and is based on feminist reflections on the life of women and men in the glocal digital public sphere in 3 Indian states, Kerala, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu.

“For women, using the social media is like riding a tiger” quipped Reeha*, a second-year graduate student from a prominent college in Kerala’s capital city. We were there to conduct a survey among students regarding technology-mediated violence against women (TMVAW). She continued, “climbing on might be easy, riding it is tough. Besides, it isn’t easy to control where the tiger’s going.” For young women like her, ‘climbing the [ICT] tiger’ was almost a rite of passage into young adulthood, but a risky passage undertaken almost all alone. No wonder many of the young women spoke of ‘stumbling’ on the way, and how the passage to becoming an individual through it was terrifying rather than exhilarating.

The simile of the tiger is indeed a revealing one. To those who are less-privileged in emerging techno-social worlds, ICTs are daunting creatures, wild and originating in hard-to-negotiate terrain. They are powerful and agile, and almost impossible to tame. Yet avoiding them may not be an option at all. This is especially so for women, and this in turn relates to the sociological changes that Kerala has experienced over the past two decades or so, in and through which many more women are questioning the social expectation that their individuation should primarily serve the ends and interests of family and community.

Given Kerala’s distinct history of public education in which more girls stay in school and public education than boys, they are likely to be far more individuated than boys. Kerala’s higher education scene is now predominantly female; successful female role-models who have fought to build spaces of their own are readily available in Kerala across diverse fields – cinema, journalism, sports, science, governance, academics, art, literature, music, and so on. However, the stratospheric rise of dowry rates across communities, well-entrenched patrifocality, as well as the valuation of the female child mainly in terms of her potential to raise the family’s social worth through marrying up has also rendered her ‘structurally worthless’. That is, the girl child, however capable she may be, cannot escape being a financial liability. The structural mechanisms that constantly work to confine the educated young woman in order to keep her marriageable are many, and they straddle domestic, community, and public spaces. Imagine what this does to the individuated woman – this silent, everyday patriarchal violence.

It is therefore not surprising that more and more young Malayali women seek the social media not just as a place to hang out but also to assert themselves as full human beings and citizens. For it appears to them that the constraints imposed on them by offline spaces may be overcome here. As a feminist lawyer who helps young women survivors of TMVAW noted, “It was not common, if you remember, for a lot of women to actively participate in public forums of debate – I mean, even if there were lots of women, for example, in student organisations’ meetings, not many would speak sharply and vociferously. Most women had no experience of speaking at a gathering, and definitely little experience in debating. That lacuna began to be felt less with online access, since women were now not constrained by time … or the challenge of having to face so many faces – faces that would be judging and evaluating even though not always hostile – in a real audience. I think that has spurred women’s ability to argue, to use strong words, and especially to use humour! This is provoking a lot of male insecurity.” The risk of ‘climbing on the [ICT] tiger’ seems worth it!

This then provokes insecurity in Malayali men, especially young men, who are now fewer in institutions of public education and by no means dominant in major fields of public achievement. The same lawyer notes perceptively the nature of mass attacks of misogynist trolling and cyberbullying of articulate young women in Kerala’s social media: “In an offline gathering, maybe an active woman would be suppressed with a couple of sharp retorts, but when it is online, you don’t know if she has really backed out. You have no way of checking if she’s really flustered, sad, contrite! So you go back again and again, get your friends to join, and keep increasing the intensity of the attack till you are satisfied, till you feel the woman has been effectively silenced! That is perhaps why these men, young and old, are so intensely violent, so unashamed of using all kinds of tactics, below-the-belt blows, in online conflict, especially when a woman is at the centre.”

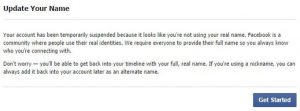

Kerala’s cyber worlds have seen mighty battles recently, led by cyberfeminists. In 2015, a group of Malayali cyberfeminists started an international campaign against Facebook’s real-names policy, which flagged women’s and minorities’ right to privacy, safety, and culture, in the wake of atrocious hate campaigns by men against a widely-followed vocal woman social commentator. A great deal of discussion followed, and while this has encouraged more and more women to enter the social media, stay back, and look at their attackers squarely in the eye, our recent research seems to show that the organization of male violence, especially on Facebook, seems to have changed for the worse. Now it appears that there are organized gangs of men who may be paid to relentlessly stalk, troll, and dox targeted women; there also seems to be organized ‘monetization’ of intimate images of women that may be available through revenge porn or through morphing images of well-known women available online into saleable porn a la Hunter Moore! These are not as explicitly justified like for instance by the Gamergate criminals or by Moore’s openly virulent misogyny, but that is hardly a consolation. The real consolation is that women seem to be steeling against such attacks, refusing to be intimidated by ‘leaks’ of their images, words, or other aspects of their private worlds, and openly refusing protectionism as an option to stay safe, as emerged in our interviews with survivors.

The disconcerting fact however appears to be that police officers, even those who would want to side with the survivors, veer too frequently into precisely protectionist discourse. Both in our interviews with them as well as in survivors’ recounting of their experiences in police stations, their chief advice to women is to avoid ‘catching the tiger by its tail’ (this appeared in casual talk preceding the interviews with police officers more than once). Once you do that, they imply, you are done – you have to follow it endlessly, for it eats you up if you don’t. Therefore do not loiter in social media. A senior police officer, known to be sympathetic to women complainants in TMVAW cases, told us: “…we are still to learn what I call cyber discipline. That refers to the ability of the person to go to the cyberworld with a pre-fixed purpose, use tech to complete it, then log out safe. Are you buying something on Amazon? Great – go there, buy, come back and log off. Don’t browse. The very concept of browsing on internet is dangerous and leads to harm.” Perhaps even more disturbing was his insistence that his concept of ‘cyber discipline’ is gender-neutral, for it seemed to cancel out the very possibility of building publics in cyberspace.

How contrary this is to young educated public-minded women’s expectations of the social media is evident from the words of a female college student who survived mass trolling across cyber spaces for her bold views. Stating her determination to maintain online presence, she noted: “The internet is so informative, the place where you get to know things – indeed I am so grateful for it, it gives us a space no one else does to grow inwardly. My response [to trolls] now is no-response – that is, I don’t care, the cyber bullies can say or do whatever they can. If they morph, fake photos, whatever, it does not affect me.” Here is a young woman who sees herself as riding the tiger, not merely being tossed about behind its tail, fully aware of risks and danger – and the pleasures.

Perhaps it is the shared simile of the tiger that we must dismantle first. The association of ICTs with the tiger and thereby with notion of wild, potentially violent, untameable masculine strength attributed to the creature is not coincidental; it is a product of the still-lingering patriarchal mystique about the Internet that sees it as hypermasculine. Riding this tiger by women could then be too readily read as foolhardiness; then injuries they may suffer could readily be attributed to their own recklessness. Yet it is clear from our research that many women are not deterred by such intimidating portrayals; that they are willing to treat it as an adventure. However, perhaps not all women have the privilege that helps them convert a danger into adventure and therefore this manner of perceiving of ICTs needs to go. We cannot help hoping against hope for the promise of ‘newness’ once held out by the social media – that its newness lies precisely in renewing our democracy, making way for the hitherto-muffled voices of underprivileged subjects.

The project, ‘Righting Gender Wrongs: A Study of Law Enforcement Responses to Online Violence Against Women’, is an ongoing exploratory research study of gender-based cyber violence led by IT for Change with feminist partners across six sites of study in India, covering the states of Kerala, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu. The research project has used mixed methods — self administered surveys with college students between the ages of 19-23, key informant interviews with law enforcement officials, women’s rights lawyers and activists, family court lawyers, counselors, digital rights activists; and focus group discussions with young men and women in colleges to study violence online as well as conduct a systematic assessment of institutional pathways to change. The intent is to make recommendations for improvements in access to justice for victims, based on robust evidence on the gaps in law, with particular focus on law enforcement agencies.The full report will be published in February, 2019. To learn more about IT for Change’s research and advocacy on the topic visit –https://projects.itforchange.net/e-vaw/

The author is with Centre for Development Studies.