Authors: Anita Gurumurthy and Amrita Vasudevan

This blog is part of the series ‘Righting Gender Wrongs’ and is based on feminist reflections on the life of women and men in the glocal digital public sphere in 3 Indian states, Kerala, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu.

In our study on the prevalence of gender-based cyber violence in Karnataka, IT for Change had the opportunity to hold focus groups discussions in Bengaluru and Mysuru with college students between the ages of 19-23. At each site, there was one all-male focus group and one all-female focus group. In this blog, voices from the groups have been juxtaposed to produce the gendered vignettes that characterize what it means for women and men to be ‘born digital’ – a term that Palfrey and Gasser use to capture the sociological portrait of a generation that is both “extraordinarily sophisticated and strangely narrow.”

Theme 1: ‘Its just a joke da1’ – Of memes and masculinity

Male voice: “Take for example if I mock or make sarcastic jokes of my friend. If it is a boy, then it is okay, but the moment I tell it to a woman, they say you’re abusing her, you’re dominating her. What is there to dominate in sarcasm? Anyone can be sarcastic, right? Women’s empowerment means equality. Men and women should be equal. So if I make a non-veg joke2 about my guy friend, that’s ok; so, if I make a non-veg joke about a girl, that should be ok. Otherwise it is unfair… hypocritical.”

Female voice: “They (men) never mean to say anything of that sort, but, they get very unnecessary memes sometimes, and we just laugh it off. We know what our personal opinions are about things, and they don’t intend to say such things.”

Female voice: “They term me as a feminist. But the term feminist is so conflicting now. It just gives a negative notion because that’s how people have made it now. But the meaning of feminism is just equality and not putting men down.”

We discussed the circulation of memes online by male students. A powerful artifact of social commentary that is often presented as humor, the meme has now firmly established itself as a medium of communication online. It is also an excellent analogy for internet culture — ephemeral and glib, sexist, but assumed to contain some ‘vague seed of truth’. The men in the focus groups invoke the language of feminism, even, patriarchy, using it as a post-feminist justification for explaining how equality is about equivalence.

According to them, labels like ‘patriarchy’ are used by women to sustain a narrative of victimhood that they don’t, or no longer, deserve. Equality is not only assumed to have been reached, but also breached, giving women an unfair leg up.

In the virality of online flows, sexualized femininity masquerading as jokes is naturalized as the commodity for masculine sub-cultures. Women friends must know that sexist jokes are just that — jokes. Women who do respond and challenge sexism are branded ‘feminist’, a pejorative that discounts their arguments. In conversations with young women, we were told that the best they could do is ignore it — “It’s sad that we’ve become so used to it that we just go ahead.”

As young men sort through content, they are able to ‘see like a feminist’. Yet, they choose to subscribe to the sexism the attention economy throws at them, using it, in fact, for the very performance of masculinity. Liking or circulating a sexist meme or sexualized picture of a classmate that she may not be aware of, is an essential rite of passage to manhood.

Theme 2: ‘Pls send nudes’ – Entitlement and control

Male voice: “Before taking nudes with a guy, the girl must think. There is no use crying now. If she was that deeply involved with him, she should have stayed in the relationship. If she cheats on him, she should know this can happen. The fact is both of them have cheated, and that is the way it is. They (women) have to think of the family before getting into the relationship.”

Female voice: “(If it happened to me) I would have been like – ‘You should have known better.’ ‘What were you thinking?’ ‘Were you in your right mind to send those pictures?’ Especially in this age of technology, we’re obviously cautioning each other.”

Female voice: “I think it’s actually come to a point where people are okay with such things. I think that’s how we’re moving on right now. Like our generation… they’re just okay with it.”

In ‘Sluts r Us: Intersections of gender, protocol and agency in the digital age’, Nishant Shah points to an important dimension of non-consensual circulation of intimate images online. The slut shaming that follows such an act is not (just) about shaming women’s sexuality but (also) the censure of women’s shamelessness — that they dared to expose themselves to the technology, stupidly allowing the artifact to be available for posterity on “the perpetual memory machine of the Web”. The easy transcendence of affairs of the private sphere into the gut of the public sphere is about male entitlement. It is the point at which the quest for liberation must meet its logical consequence. If women throw caution to the winds, they are bound to be shown that they have breached the gender protocol.

The men we spoke to express similar approaches to intimacy through tech-mediated spaces. While sending a man risque pictures, a woman should have known that it will be leaked if she steps out of line – for instance, by breaking off the relationship – and that it’s all fair game. ‘Hidden cameras’ and recording women clandestinely, cases wherein women’s agency is passive, on the other hand, elicits a more sympathetic response — the perception that her ‘modesty has been outraged’. However, this does not accommodate the very negation of women’s consent in such an act. In our conversations on ‘revenge porn’ with women, the ubiquity of these acts became apparent. Again, while no judgment is passed about engaging in sexual acts, regret is expressed for perceived shortsightedness in allowing oneself to be captured in the act. A surprising outcome of the pervasiveness of ‘revenge porn’ is that women today are able to brush it off with a, “So what, it’s just my body. Who cares!” Shame and guilt it would seem are not always seen as feminine burdens that women in patriarchal orders must carry. If this is a one-off remark or a comment from someone empowered will need to be better understood. However, what is clear is that the ignominy of public exposure, the experience of fear and indignity attached to the denial of consent are real for the majority, and need to be addressed.

Theme 3: ‘Your safety is in your hands’– Self-discipline and techno-fixes

Male voice: “But girls also should keep their accounts private and within their friends’ circle. There are faults in them as well. Girls should be more careful. If they are concerned, why aren’t they more careful? There are a lot of ways to do this now. You can share things with only a group of friends. But girls want likes and fame. That may be a problem.”

Female voice: “ You can control the kind of content you’re following. But, it also depends on the kind of people on the Internet. You can’t stop these people from existing. When you think about it, what you can do personally is small changes in your privacy settings.”

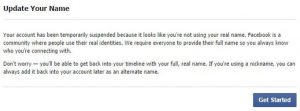

Female voice: “Websites should make people submit their Aadhaar details so that we can immediately get to know all their information, report and block them… and arrest those who misuse screenshots. At least the person will be scared that they can’t misuse pictures.”

The men betray a deep discomfort with the visibility of women in online spaces, especially in cases of image based self-representation, a decidedly agentic exercise. As a consequence, when women post selfies or pictures, they are inevitably sexualized, and blame associated with sexual expression is evoked to deride the violation of gender scripts. The ‘good girl’s’ narrative does not include garnering likes or going after popularity. This presents, as Salter observes, ‘an incompatible demand’ that young women should not be sluts, but should also not be prudes.

Public spaces have historically been unwelcoming of women, and women who do stray into the public have no choice but to accept any deprecatory ascriptions that, in all likelihood, will follow. Gender norms on mobility and visibility on the Internet are seamlessly tied to cultures of female responsibility and self-discipline. Women are told to build walled gardens through technological aides, so that they can remain online and benefit from the wonders of technology without encountering any of the harm. While some women resign to this discourse, others demand technology be underwritten by identification — for access to some form of security.

For digital corporations, these are ideal responses, allowing them to occupy the position of the ‘innocent by-stander’ or the ‘willing conduit’, that have no control over the core content, but are ever-willing to tweak the edges. The evolution of the Internet and the rise of culture as visual rhapsody, carefully engineered by deliberate design choices of platforms should tell us otherwise. Those who are born digital, are born into the rapid replacement of textual content by image based, user generated content. When the burden of creating safe spaces is displaced on users, it falls on the shoulders of those that demand safe spaces in the first place, i.e. women and others from marginalized locations, to effectuate it. And when their demands aren’t met, which is invariably the case, they have no choice but to give in to the disciplining force of violence, by self-censoring.

For feminists fighting for safe online public spaces, confronting the complicity of digital platforms in cementing gender norms is as important as challenging hypermasculinites.

The project, ‘Righting Gender Wrongs: A Study of Law Enforcement Responses to Online Violence Against Women’, is an ongoing exploratory research study of gender-based cyber violence led by IT for Change with feminist partners across six sites of study in India, covering the states of Kerala, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu. The research project has used mixed methods — self administered surveys with college students between the ages of 19-23, key informant interviews with law enforcement officials, women’s rights lawyers and activists, family court lawyers, counselors, digital rights activists; and focus group discussions with young men and women in colleges to study violence online as well as conduct a systematic assessment of institutional pathways to change. The intent is to make recommendations for improvements in access to justice for victims, based on robust evidence on the gaps in law, with particular focus on law enforcement agencies.The full report will be published in February, 2019. To learn more about IT for Change’s research and advocacy on the topic visit –https://projects.itforchange.net/e-vaw/

The authors are with IT for Change.